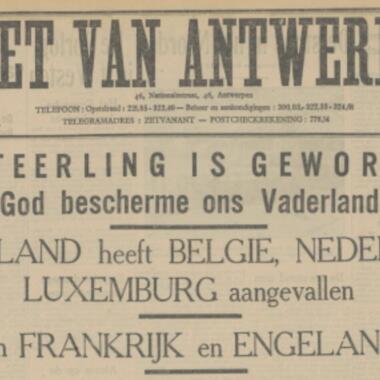

1 September 1939

The beginning of World War II

On 1 September 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland. A few days later, the United Kingdom and France declared war on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany. On 10 May, German forces invaded Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and France. The months between September 1939 and the invasion are known as the Phoney War.

10 May 1940

The first aerial strikes on Antwerp

The Luftwaffe bombards Deurne Airport. The bombs also struck the Sint-Amadeus mental institution. Several civilians perished.

13 May 1940

The deportation of May 1940

The Belgian authorities also ordered the internment of alleged collaborators at the time of the German invasion. Many of them were foreigners (Germans and Eastern Europeans), communists and even anti-fascists. But they also arrested several prominent national-socialists, members of the Rexist Party and radical Flemish nationalists. On 13 May, several people were deported from the Antwerp prison in Begijnenstraat, including among others August Borms, René Lagrou, René Lambrichts, Jan Timmermans, Ward Hermans. The latter returned to Antwerp soon after. Many of the Jewish deportees remained in the internment camps in the south of France, however.

14-15 May 1940

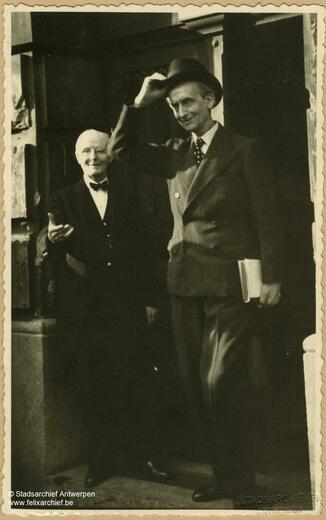

A repeat of 1914? Antwerp flees

With the horrific events of World War I still fresh in many people’s minds, a large part of Antwerp’s civilian population fled the city. The socialist mayor Camille Huysmans also left the city, along with three other aldermen. He travelled through France to London, following in the footsteps of the government and other MPs. Leo Delwaide, the catholic alderman for the port, became the new mayor.

18 May 1940

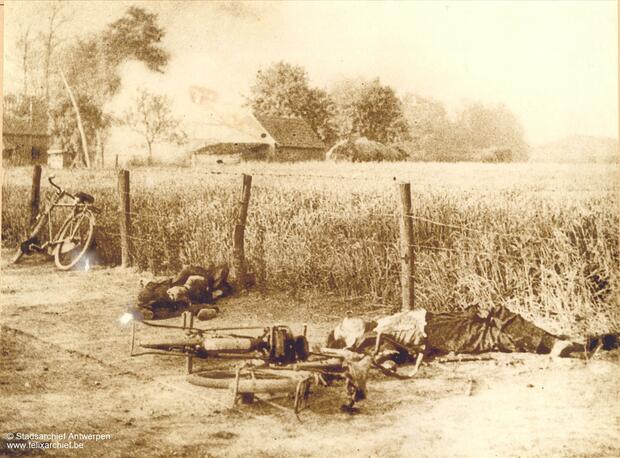

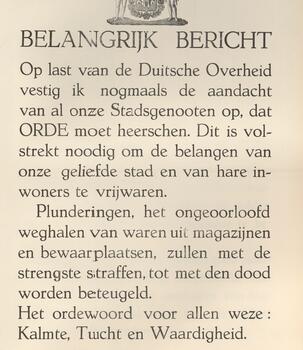

Occupied city

The German forces occupied the city. The city fell without a struggle. The people of Antwerp did their best to adapt to daily life under military occupation. It was anything but easy. The press was censored. Nazi flags popped up here and there in the city, as did German soldiers. People’s freedom was curtailed.

28 May 1940

The surrender

After 18 days, the Belgian army, under the command of King Leopold III, surrendered. The Belgian government expressed anger at the king’s decision to capitulate, as they wanted to continue fighting. In the meantime, the Germans occupied Belgium and installed a military government. Congo, Belgium’s colony, was not occupied.

Summer and autumn of 1940

Resistance

It soon became clear, from small ‘acts of resistance’, that some Antwerpers refused to surrender to the Germans. On 18 May, a local trader called Louis Pighini succeeded in stealing the Nazi flag from the Cathedral. Others took part in small-scale sabotage operations, destroying the phone lines of the Germans for example. They also organised actions on symbolic occasions, such as the national holiday or Armistice Day (11 November). Some Antwerpers pinned Belgian flags to their lapels or laid flowers at the monument to King Albert I, the King of the Belgians during World War I. German posters in the city warned the population that any resistance would be repressed.

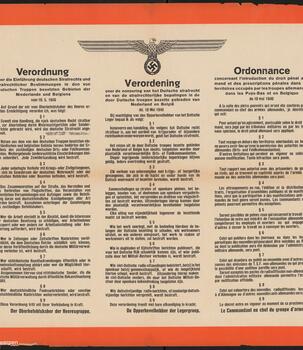

Second half of May 1940

The foreign invaders take over

The German government, administration and police forces, such as the Sicherheitsdienst SD (Della Faillelaan and later also in Koningin Elisabethlei), installed themselves in the city. The Feldkommandantur 520 (Pelikaanstraat and later Meir) was in charge of day-to-day management. The Germans also appointed a Stadtkommissar. The latter established good relations with the town hall and mayor Leo Delwaide. The cooperation run very smoothly.

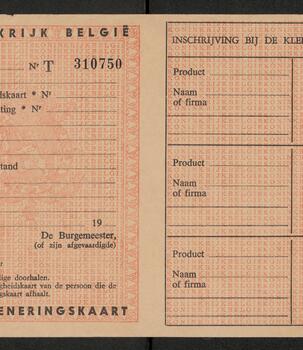

Early June 1940

Daily bread

Food, or the lack thereof, had the greatest impact by far on daily life in occupied Antwerp. Soon there were serious food shortages. As of May 1940, Antwerp, like many other cities, instituted a coupon system. Food was rationed and the food purchases were heavily regulated. For the next five years, coupons and ration books - provided by the city or other aid organisations - became a precious commodity. Although you could not use them to pay for food, these coupons proved that you were entitled to a specific product. The city’s festival hall in Meir was the central collection point. It was often incredibly busy.

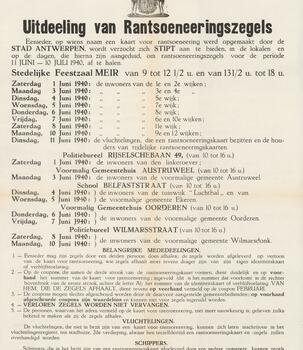

15 July 1940

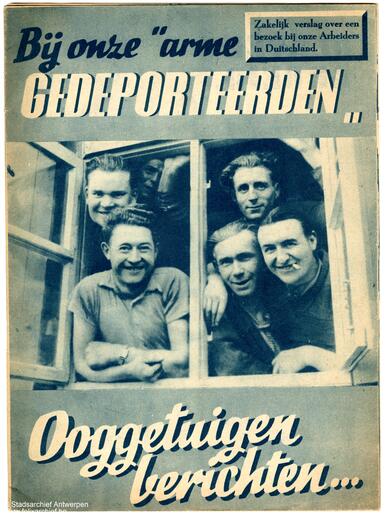

Voluntary employment

In an attempt to solve the high level of unemployment, the Germans sought to employ Belgian workers as part of the German war effort. As of July 1940, Antwerpers were encouraged to go work in Germany on a ‘voluntary’ basis. The Germans tried to lure workers with higher wages and attractive employment conditions. Some people felt they did not have any other alternative if they wanted to make it through the war. Others caved in under the pressure from the employment agencies that recruited them. A first convoy of 1,000 Antwerp workers departed from Antwerp’s Central Station on 15 July. Four months later, over 50,000 had left.

August 1940

The collaborators attempt to seize power

Jan Grauls was appointed Governor of the Province of Antwerp. He replaced Georges Holvoet, who had fled to France. On paper, Grauls was not affiliated with any political party. In practice, however, he supported the New Order. He also espoused the ideas of political collaboration of the Vlaams Nationaal Verbond (albeit in a more moderate way). This Flemish nationalist political party, which received 12.5% of the Flemish vote before the war, decided to collaborate with the Germans early on in the war. They hoped to be appointed to important jobs in government. In 1942, Grauls became the mayor of Greater-Brussels. Frans Wildiers, a staunch supporter of the VNV, took over from him as Governor of Antwerp.

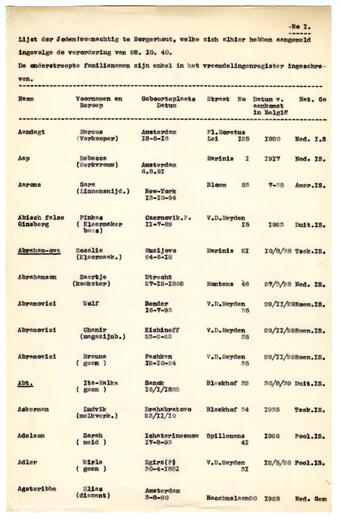

October 1940

The first anti-Jewish measures

The city had a large Jewish community. Many of them were foreigners. In the years prior to the war, many refugees from Nazi Germany and Eastern Europe, who fled violence and persecution in their native countries, also moved to the city. The first anti-Jewish measures also affected them. They included a ban on ritual slaughter and also forbade Jews from exercising certain professions. They also prevented Jews who fled during the invasion from returning to the city. Before December 1940, Jews aged 15 years or older who lived in the city were forced to register with the administration. The town council actively cooperated, calling on Jews in the city to register. They took care of the registration. Police officers helped draw up the lists.

29 October 1940

Winterhulp

The food and aid organisation ‘Winterhulp’ (Secours d’Hiver) opened a branch in the city. This was the Ministry of Public Health’s ‘official’ response to the food shortage. The German Militärverwaltung supported this organisation, which had branches all over the country and which worked very closely with the local authorities. In Antwerp, Winterhulp also distributed food in several places throughout the city.

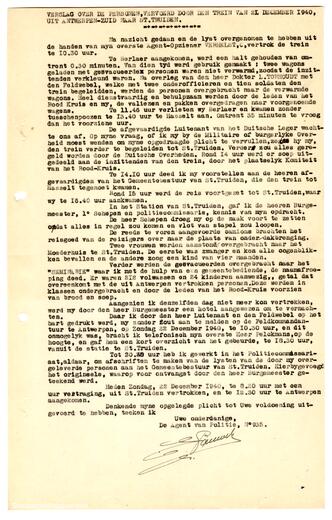

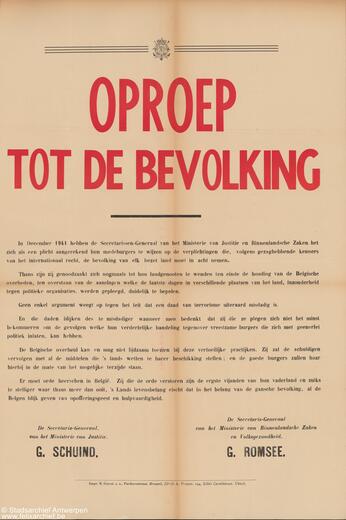

December 1940

Deportations to Limburg

From end December until early February, nine trains departed from Antwerpen-Zuid station to Limburg, with just under 3,000 Antwerp Jews and other foreigners on board. The occupying forces had rounded them up for forced labour. Antwerp’s police force distributed the deportation orders and accompanied them to the train station.

Autumn 1940 - Spring 1941

‘Flamenpolitik’

Flemish prisoners of war return from Germany. As part of their Flamenpolitik, the Germans decided to exclusively grant this favour to the Flemish (and not to the Walloons). They hoped this would increase the support from the Flemish movement and population.

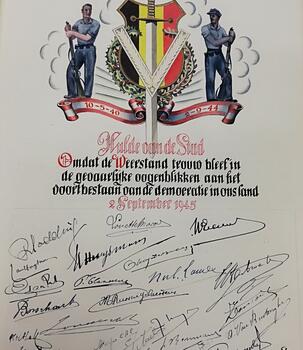

End of 1940

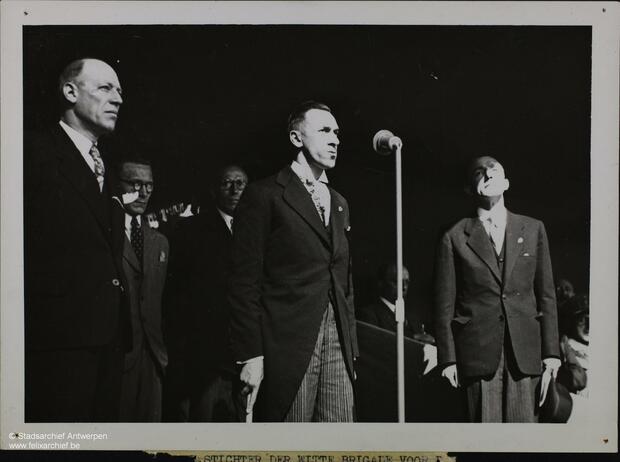

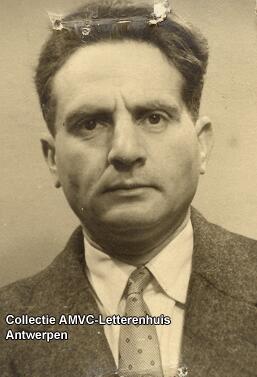

Marcel Louette founds the White Brigade

School teacher Marcel Louette founded a resistance group in Antwerp, which would become the White Brigade. The name referred to their opposition against the ‘black’ brigade of collaborators. The group consisted of port workers, teachers and police officers. They published clandestine newspapers, tried to collect information and established lists with names of collaborators. Many of the members were arrested. In May 1944, the Germans succeeded in capturing Louette. He was locked up in Breendonk, where he was tortured and then put on a transport to Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg. He subsequently returned from the camps.

End 1940, early 1941

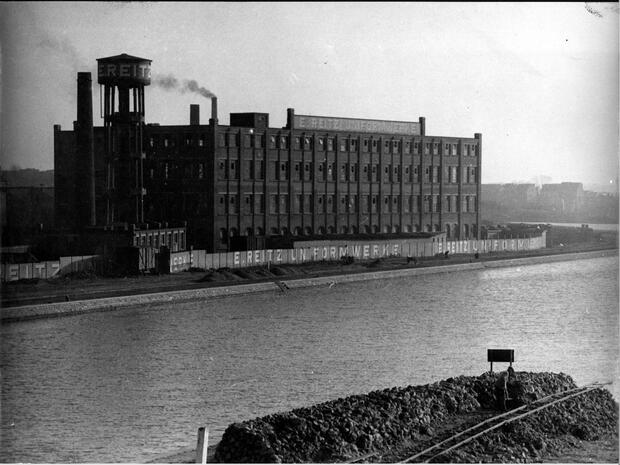

Working for the ‘Reich’

The German administration took over Belgian factories and started up its own production lines. This was all part of the German war effort. At the end of 1940, the Germans in Mortsel transformed the old Minerva factory in Mortsel into an aircraft maintenance plant, called ‘Erla’. As of early 1941, the textile machines of ‘Reitz Uniformwerke’ were running at maximum capacity in the plant along the Albert Canal in Merksem.

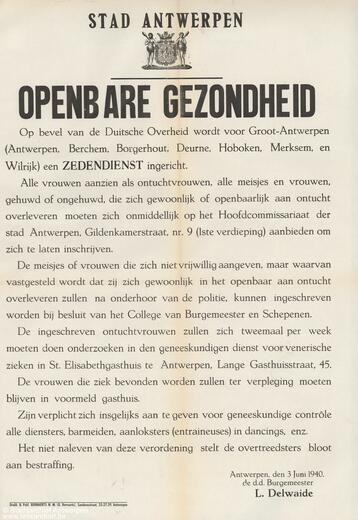

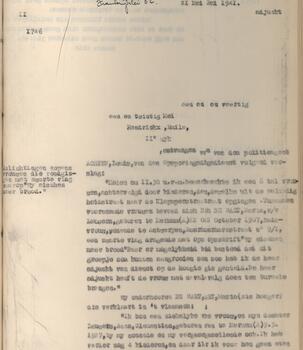

17 January 1941

Depravity

The presence of German troops in the city led to an increase in prostitution. German and Belgian medical services tightened their controls to avoid ‘depravity’ with additional checks and obligations.

Spring of 1941

Social unrest

The social tensions were exacerbated due to the bread crisis and the rising food shortages. On 23 March, a group of working-class women protested in front of the town hall of Berchem with a black flag. This was the prelude to a series of larger public protests in Antwerp’s Grote Markt on or around 21 May. Working-class women from the 5th and 11th districts clamoured for more and affordable bread as well as more rigorous price controls, under the instigation, among others, of militant communists. By then food prices had already increased by 75%. But food cost several times that on the black market. Mayor Delwaide was forced to take action. A few days later, he received a delegation of the women in his office.

Mid-April 1941

Anti-Semitic violence

After several small-scale actions against Jews in the city in previous days, public violence erupted in the ‘Jewish’ 6th district near Antwerp’s Central Station on Easter Monday (14 April). The crowd erupted after a screening of the propaganda film Der ewige Jude by the radical anti-Jewish group Volksverwering. Two hundred Antwerpers and Germans joined in the pogrom. They destroyed the home of a rabbi and set fire to the synagogues in Van Den Nestlei and Oostenstraat. They pillaged the synagogues and prevented the firemen from extinguishing the fire. Several windows were broken in the Jewish district and shops and property destroyed. They left a trail of destruction in their wake.

31 May 1941

New anti-Jewish ordinances and measures

The Jews in the city were now forced to declare their real estate, bank accounts and other securities to the German administration. Jewish companies came under German management. Two months later, the Board of the Antwerp Bar deleted the names of 17 of their Jewish colleagues and trainee lawyers from the list of lawyers.

22 June 1941

Operation Barbarossa: Germany invades the Soviet Union.

Now the communists were the enemy. The German repression in occupied Belgium was merciless (Operation Sonnewende). Several arrests were also made in Antwerp. The communists organised themselves for underground activity. In the meantime, pro-German groups of collaborators started to recruit (Flemish-nationalist) men to fight on the Eastern Front.

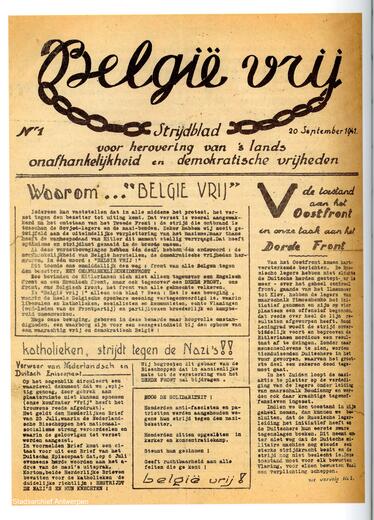

Summer of 1941

“Nothing for Hitler, our food for us”

Pamphlets were distributed in the city. They were published by the communist-inspired resistance organisation, the Onafhankelijkheidsfront (OF). This organisation gradually garnered more support in Antwerp, fuelling the social unrest. They distributed the clandestine newspaper ‘België vrij’.

July 1941

Antwerp’s police force

Chief of police Jozef De Potter returns to Antwerp after fleeing the city at the beginning of the war. He replaced Gustaaf Zwaenepoel who had taken over his job. Six months later, the catholic magistrate Edouard Baers took up his new position. He replaced public prosecutor De Schepper, who was forced to step down because of his age.

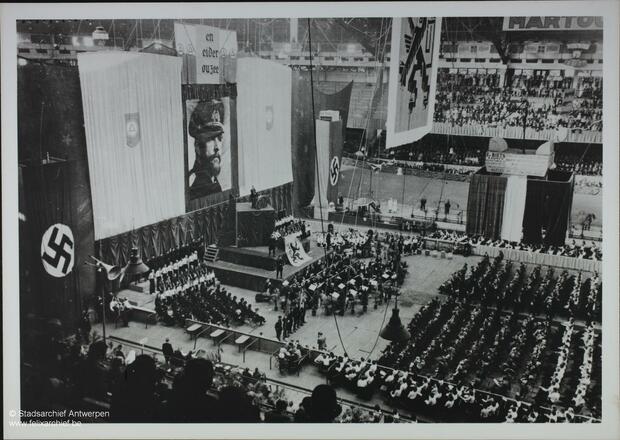

20 July 1941

Meetings in Sportpaleis

Staf De Clercq, the leader of the VNV, gives a speech to a huge crowd in Sportpaleis. He called on the young people of Antwerp to join the Flemish legion and fight on the Eastern Front.

21 July 1941

Riots in the city

In 1941, there were more skirmishes on public holidays, including on 21 July and 11 November. At night, people daubed trees and walls with V(ictory) signs. Belgian patriots, wearing Belgian ribbons, insignia and flags, clashed with groups of collaborators (members of the VNV, Vlaamse Wachters, SS men...).

29 July 1941

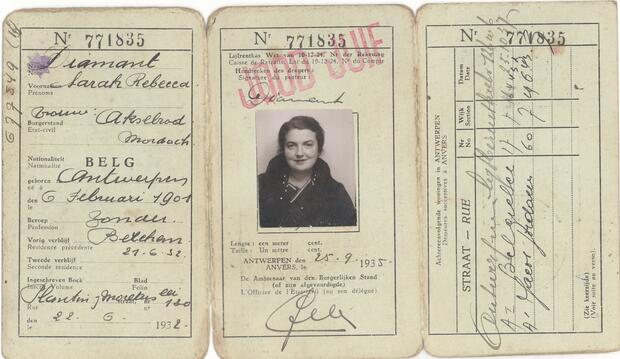

From this date, all Jewish ID cards were stamped with the word ‘Jood-Juif’.

August 1941

Replacement of Alderman E. Sasse

The German administration had liberal alderman Eric Sasse removed from office. Rumour had it that he was replaced because his son was a member of the resistance. But the occupying forces also targeted him because he was freemason. Earlier that summer, in 1940, German officers searched the masonic lodges. They packed up 29 crates of books and valuable objects, which were then sent to Berlin. The freemasons were disbanded at the end of 1941 by the Germans.

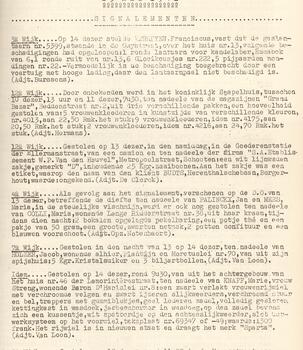

November 1941

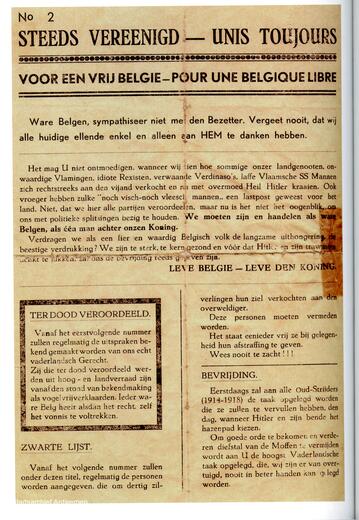

Resistance newspapers

The pioneers of Antwerp’s resistance press, the Cutzen brothers, were arrested by the German Sicherheitspolizei, along with some of their collaborators. They published a clandestine pamphlet called ‘Steeds Vereenigd/Unis Toujours’ since January 1941. One of the brothers died while being deported to Siegburg in Germany. The newspaper itself was published again as of 1942 by the White Brigade.

25 November 1941

A new Jewish organisation

The Vereniging der Joden in België (Association of Jews in Belgium) was founded on the Germans’ orders. All Jews in the city were forced to join this association. The daily management of these ‘Jewish councils’ was in hands of prominent Jews. The association itself was supervised by the Ministry of the Interior and the Germans. VNV collaborator Gerard Romsée had been appointed as the organisation’s secretary-general a few months earlier. He passed on all the information that was gathered to the German administration.

1 December 1941

The Jews are banned from non-jewish schools

The Germans issued a law against overcrowding in schools, which henceforth prevented Jewish children from attending school in general public institutions.

7 December 1941

The United States enters World War II

Japan, a German ally, attacks the naval base at Pearl Harbor. The United States declared war on the Empire of Japan, and officially entered World War II.

End of 1941

The emerging resistance is dealt a blow

From February until April 1941, a spy called Emmanuel Hobben succeeded in establishing radio contact with London (the Williams network) on British orders. He wanted to pass on information about the port to the Allied forces. This proved very difficult and even impossible at times. The Germans soon zeroed in on the group around Hobben. The verdict was terrible. The occupying forces arrested and sentenced 26 employees in Antwerp. Ten of them, including Hobben and several journalists of the resistance newspaper Le Clan d’Estin, were executed one year later in Berlin.

The winter of 1941-1942

A harsh and cold winter

It froze non-stop from December 1941 until March 1942. The winter was incredibly harsh and cold. Antwerp was freezing. There was a shortage of coal. People gathered in the city’s public halls where they could warm up. Emerging resistance organisations such as Onafhankelijkheidsfront capitalised on this, fuelling resentment about the occupation. The anti-German sentiment increased steadily. But the people also voiced their anger about the king, the British and the war.

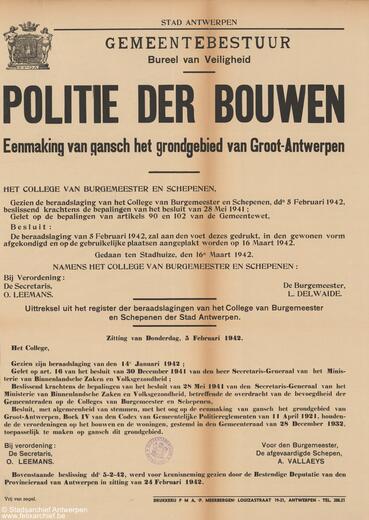

1 January 1942

Greater-Antwerp is officially established

In the summer of 1940, the German commander in Antwerp started to prepare this change, although he met with opposition in government circles in Brussels. They rightly asserted that it was completely illegal to annex the suburbs. The Antwerp town council, and Mayor Leo Delwaide especially, had no problems with this however, which is why they forged on. The port authorities and other economic players were also in favour of the decision. The decision was published in the Belgian National Gazette in mid-September. Five months later, the suburbs of Berchem, Borgerhout, Deurne, Hoboken, Merksem, Mortsel, Wilrijk and part of Ekeren merged with Antwerp. Their municipal councils were abolished and so were the municipalities.

1 January 1942

A new town council (for Greater-Antwerp)

The new council of aldermen was made up of 8 members of the Old Order and 5 members of the New Order. Two ambitious members of the VNV, Jan Timmermans and Rob Van Roosbroeck, were appointed as aldermen. Mayor Delwaide retained the trust of the Germans. His authority was legitimate and the collaboration continued without any significant problems.

3 January 1942

Radio banned

Listening to the radio was banned. The Germans hoped to prevent the population from listening to illegal radio broadcasts and British radio stations.

23 January 1942

A new wave of arrests in the port

The SIPO-SD cracked down on the communists. Several arrests were made in the port from 1942 onwards. Workers of the Mercantile and Beliard shipyards and the Inter-Escaut factory died. A total of 64 people were arrested, 25 of whom died.

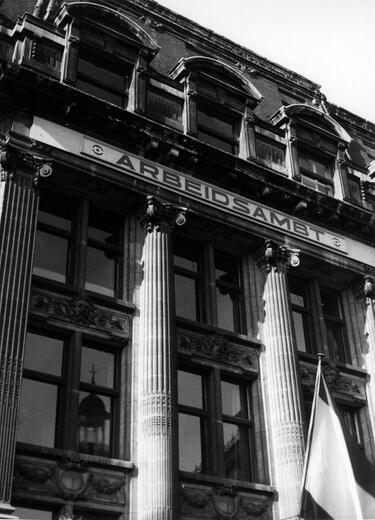

6 March 1942

Beginning of forced labour in Belgium

For the time being Antwerpers could only be forced to work in Belgium. But how long would it be before the Germans would start to send people to Germany? In theory, every Antwerper could be forced to accept any job. The Belgische Rijksarbeidsambt (RAA, Belgian National Employment Agency) (headquarters in Antwerp at Cockerillkaai, in the south of the city) was established in April and helped execute this measure. The agency was led by proponents of the New Order. The Germans oversaw the agency’s activities. Mayors were also asked to provide lists of names of the unemployed and other ‘anti-social elements’ such as smugglers and people who refused to work.

March - April 1942

New measures target the Jewish economic activities.

All rough and polished diamonds had to be declared to the ‘Diamond Control’ of the occupying forces. All Jewish companies that were affiliated with the Diamond Control were soon forced to stop trading. This led to a liquidation of Jewish activities in Antwerp’s diamond trade.

22 April 1942

German Jews in occupied Belgium lost their nationality

Many of these Jews had arrived in Belgium in the 1930s. They had fled the violence and the Nazis in Germany.

1 May 1942

Labour Day

Members of the communist resistance (Partisans) planned actions on ‘their’ day. They targeted the homes of three prominent members of the VNV with grenades.

8 May 1942

Forced labour for the Jews

From May until September 1942, the Germans forced Jews to go work in northern France. The Jews were recruited by the employment agencies. The local police forces helped distribute the conscription forms. The Antwerp police force also accompanied the Jewish unfree labourers to the train stations. They worked on the Atlantikwall and other German military building projects in labour camps of Organisation Todt. The working conditions were downright appalling. At the end of October of that same year, the labour camps were evacuated. Most of these ‘OT Jews’, historians estimate approximately 80% ended up in Auschwitz via Mechelen.

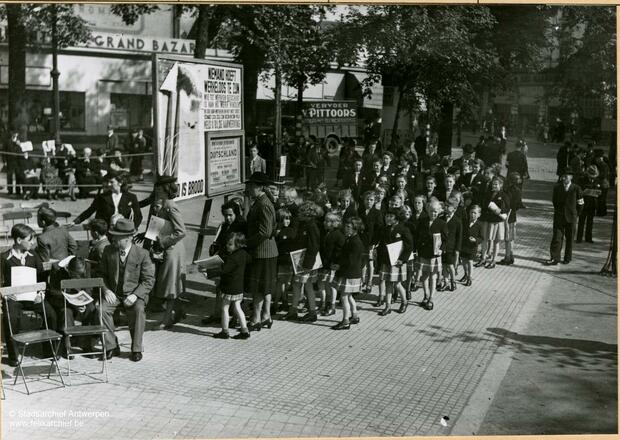

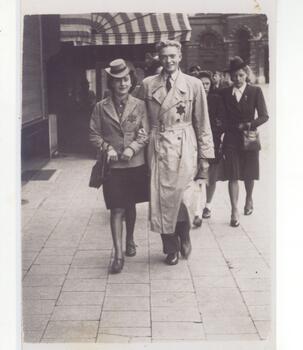

11-15 June 1942

Introduction of the Yellow Patch

As of 11 June, Antwerp Jews were required to collect their yellow patch, or a yellow star, in the schools in Provinciestraat, Belgiëlei and Grote Hondstraat. The Germans gave the orders, but the city’s administration was in charge of the distribution and registration of the patches. All Jews aged six years or older were forced to wear this yellow patch. The administration drew up lists of all Jews who did not collect a star. The administration distributed approximately 15,000 of these patches.

Mid-July 1942

New anti-Jewish measures

By mid-July, Jews were banned from entering the city’s parks, cinemas and theatres. Access to trams was restricted to the platforms of the tramcars. They were also banned from leaving their home between 8 pm and 7 am. And finally they were no longer allowed to practice medicine. From mid-August, Jews could only go to Sint-Erasmus hospital in Borgerhout.

22 July – 14 August 1942

The run-up to the raids

The Antwerp branch of the Vereniging voor Joden in België (VJB) was tasked with distributing ‘Arbeitseinsatzbefehlen’ to the Jews. They were informed that they had to register at the Dossinkazerne in Mechelen for forced labour. The Jewish community did not heed these orders.

22-23 July 1942

First raid on the Jews

That day, the first forced arrests and deportations of Jews in and around Antwerp took place. German officers of the Sicherheitspolizei arrested a few hundred Jews who arrived in Central Station from Brussels on those two days. A similar raid took place nearby, in Pelikaanstraat.

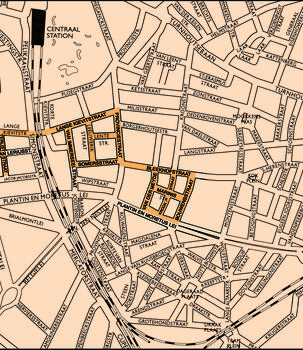

13-14-15-16 August 1942

The second and third raid on the Jews

In the night of 13 and 14 August, German officers rounded up 206 Jews, including 53 children. Many of them were Eastern European Jews.

The next day, another large-scale raid took place. This was also the first time that the local police publicly aided the Germans. Antwerp police officers helped shut down streets and accompanied the Jews to the nearby trucks. German officers raided homes, brutally dragging the occupants out onto the street. They often roughly loaded the Jews onto military trucks. The raid took place in two locations. The first raid centred on Lange Kievitstraat, Provinciestraat, Somersstraat and Van Immerseelstraat. The second raid focused on Bleekhofstraat, Van der Meydenstraat, Plantin en Moretuslei and Bouwmeestersstraat. The raids lasted all night. An estimated 1,000 Jews were rounded up. Mayor Delwaide and public prosecutor Baers stayed mum. They refused to comment on the events. They were formally informed about the raids however because of the police reports.

27 August 1942

Sabotage

The Germans spent the whole day planning a new raid. This was cancelled at the last minute. Allegedly some Antwerp police officers informed the Jews in the city about the impending raid. Warning notes were also found. While some officers had been bribed, others followed their instincts. The dividing line is not always clear. Jews fled or went into hiding.

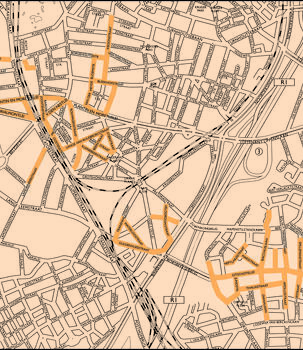

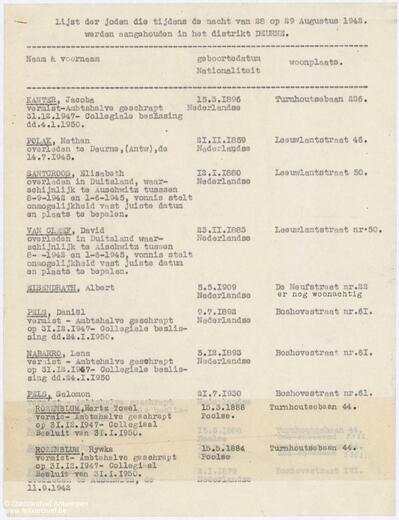

28-29 August 1942

The fourth raid on the Jews

As punishment for sabotaging the raid the day before, Antwerp’s police force was forced to play a more active role in this raid. They were ordered to arrest 1,000 Jews. Orders were given to police officers from the 7th district (Deurne, Borgerhout and Berchem). The commissioners had a difficult time finding a sufficient number of officers to carry out the raid. Chief of Police De Potter declared without hesitation that the orders had to be followed. Some officers refused to take part, others chose to turn a blind eye here and there. Other units provided reinforcements. The agreement was that 250 Jews would be arrested in every district. Those units that failed to round up this number continued their search in other districts. Police officers from Deurne searched the 6th district for example to achieve their target. The raids lasted all night. The arrested Jews, who were rounded up in the schools in Grote Hondstraat (Zurenborg) and Vinçottestraat (Borgerhout) or Cinema Plaza (Gallifortlei, Deurne), were petrified. That morning, the first trucks left for the ‘transit camp’, the Dossinkazerne. From there they travelled to the Auschwitz concentration camp. The local Judenabteilung and the Antwerp Jew hunters considered the mission to be successful. They were elated. Once again, Antwerp’s local government did not respond.

1 September 1942

The socialist alderman Adolf Molter resigned from office.

He officially expressed his ‘conscientious objection’. Did he resign because of the deportations of Jews? He had not attended the meetings of the council of aldermen for several weeks already.

11-12 September 1942

The 5th raid on the Jews

That day, the Germans did not count on any support from Antwerp’s police force. Nonetheless, several police offers assisted their German colleagues during these raids. They rounded up Jews in various locations in the city, placing them on transports. People were literally plucked off the streets here and there. This raid was clearly less systematic, and the actions were more random. It was very efficient nonetheless. That day alone, the occupying forces rounded up 700 Jews. The raid continued in the days, weeks and months after this. More and more Flemish SS men helped search for Jews on the streets. Others were betrayed.

Summer and autumn of 1942

Assistance to the Jews

The city’s population already provided assistance to the Jews during the raids. These were unstructured efforts, by individuals, such as neighbours, acquaintances or friends. They sheltered people and helped them go into hiding, took care of their children or helped them flee the city. Others provided financial support or food, in an attempt to help. The initiatives became more organised and widespread over time.

20 September 1942

Antwerp: the stronghold of the collaboration

The VNV, DeVlag and other pro-German parties and groups had a lot of support in Antwerp. Notwithstanding the fact that their members and sympathisers only accounted for 10 to 15% of the population, they organised meetings and had a very visible presence on Antwerp’s streets with their many marches. On 22 September, another major meeting was organised in Antwerp’s Sportpaleis in honour of Staf De Clercq. He was the leading man of the VNV. But not for long. He died soon after. Hendrik Elias became the new leader. He also visited Antwerp often.

6 October 1942

Forced labour in Germany

Seven months later, the time had finally come. An ordinance now also announced forced labour in Germany. For many people in Antwerp, this was the ordinance they hated the most. The discontent was palpable. Many people remembered the stories of cruelty and forced employment in Germany during World War I, which is why they decided to go in hiding. Those who went in hiding or attempted to do so automatically ended up with the resistance. All men between the ages of 18 and 50 years of age were eligible to work in Germany. Some groups were able to avoid this, such as collaborators or workers who already worked in the war industry, which was deemed inexcusable.

20-21 November 1942

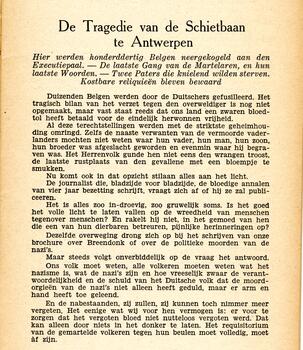

The occupying forces executed members of the resistance

As of July of that year, the Germans used the shooting range in D’Herbouvillekaai (near hangar 9A) as a place to stage their executions. Post-war testimonials attest that approximately 130 Belgians were killed here. That November, the Germans executed eight members of the Antwerp resistance. They were part of the Stockmans information network, named after Charles Stockmans, an Antwerp industrialist and master printer. From December 1941 until June 1942, the group tried to spy on and pass on information to representatives of Free France in London. They recruited helpers in the Compagnie Maritime Belge among others.

27 November 1942

A murder in Brusselschestraat

Three members of the resistance killed Hendrik Selleslaghs, a police officer and deputy commissioner of the 6th district. He was said to be pro-German and pro the New Order. The occupiers announced reprisals just a few weeks later. Ten communist prisoners were killed in retaliation.

End of 1942, early 1943

A turning point in the war

This was a tipping point. The impact of military events in Northern Africa, the Mediterranean and on the Eastern Front proved far-reaching. The German General Rommel was defeated at El-Alamein in Egypt (October – November 1942). The Soviets defeated the Germans at Stalingrad (February 1943). The occupying forces started to feel the heat. The government in exile in London and the local authorities in Antwerp also felt the heat.

3 December 1942

The town council protests

The town council informed the German administration that they refused to collaborate with the forced labour. Mayor Delwaide categorically refused to share the lists of names of municipal workers with the administration. The occupiers ended up using the civil registries to establish their own lists. In January and February of 1943, the occupying forces conscripted 530 city workers from various municipal departments to go forcibly work in Germany. The town council also protested against other things, including the many seizures of goods in the port.

17 December 1942

New legislative orders to punish collaboration

The Belgian government in exile also analysed the changed military situation. The Allies clearly had the upper hand by now. The idea of a so-called compromise peace was definitively dismissed in London. The consensus in government circles was that a strong signal of support had to be sent to occupied Belgium. The government in exile thus announced that it would increase the penalties for political collaboration. The news increased the pressure on Belgian administrators in the occupied territory.

End of 1942 – May 1943

A spiral of violence in Antwerp

Since the defeat at Stalingrad and the introduction of forced labour, the number of actions of sabotage and (violent) actions by members of the resistance had increased steadily. The Germans cracked down on them, making dozens of arrests. Groups of collaborators retaliated. They marched through the city, leaving a trail of destruction in their wake. March, April and May 1943 were especially violent.

8 February 1943

Murder of former alderman Eric Sasse

One well-known victim of this spiral of increasing violence was the former liberal alderman Eric Sasse. He was killed by men of the storm troops under the command of the Flemish SS Sturmbannführer Robert Verbelen.

April 1943

New arrests

The leaders of the Flemish Communist Party were arrested in Antwerp, including their strongman Jef Van Extergem. They were sent to Breendonk and were later deported to the concentration camps, where Van Extergem died of deprivation.

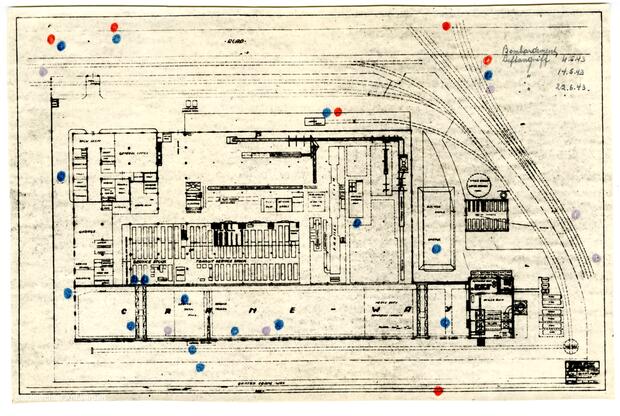

5 April 1943

Allied bombs on Mortsel

The Americans bomb Mortsel. The Americans were targetting the German ERLA aircraft factory, but the bombs missed their target, falling on the centre of Mortsel (Oude God), the Gevaert factory and a school instead. A total of 936 people died, including 209 children. The German propaganda machine saw this as a great opportunity to discredit the Allied bombardments.

15 May 1943

New air raids by the Allied forces

For the first time, Allied planes dropped bombs on the factories of Ford and General Motors, which produced products for the German economy. The attacks continued in June and September later that year.

8 June 1943

Pillage of the mayor’s residence

A group of collaborators called ‘Vlaams Legioen’ (Flemish Legion) collected money for the families of the victims of the bombing of Mortsel. However Leo Delwaide refused to officially receive them at the town hall. The hotheads therefore decided to take out their anger on his home and furniture in Vrijheidsstraat.

Second half of 1943

The Joodsch Verdedigingscomiteit is established.

The Jews also started to organise themselves. This proved more difficult however. Many Jews had already been deported. A resistance group, called the Jewish Defence Committee, was founded in extreme left-wing circles. The committee was established in the summer of 1942 and as the war progressed it gradually became part of the Onafhankelijkheidsfront/Independence Front. The committee had a lot of support in Brussels and Charleroi especially. In Antwerp, a first full-fledged branch was only founded at the end of 1943. Essentially, it was a combination of various already existing resistance groups. They arranged assistance, hiding places, food and money. The protagonists of this Jewish resistance group, which was called the Comité ter Verdediging van de Joden, were Abraham Manaster, Josef Sterngold and Leopold Flam.

3 and 4 September 1943

Raid on Belgian Jews Iltis plan

A last major raid in Antwerp by the German police. This raid was part of the Iltis plan. Unlike the first raids in Antwerp, the German police and their staff now also targeted Belgian Jews. Until then, they had largely been saved from deportation. After this raid, the occupying forces formally declared Antwerp to be ‘Judenrein’. Historians conducting research into the Holocaust in Belgium often refer to the ‘Antwerp specificity’. This means that the Jewish population in Antwerp was proportionately more at risk than Jews in other Belgian cities - for various reasons.

26 September 1943

The 10th anniversary of the VNV

VNV strongman Hendrik Elias gave a speech in Grote Markt. It was a costly affair. Parades were organised and flags handed over.

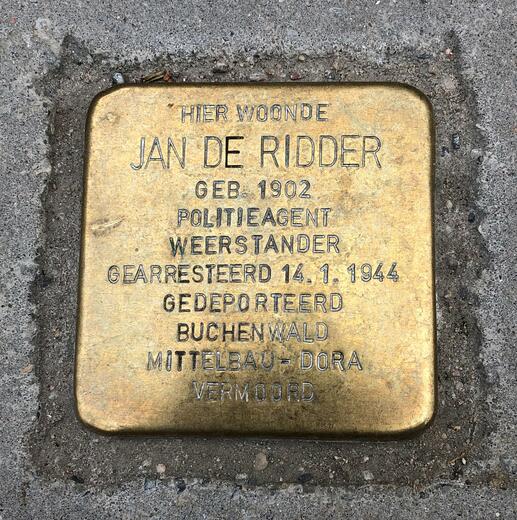

14-15 January 1944

Arrest of police offers

On these dates, the German Sicherheitspolizei arrested 75 officers of the Deurne police force. Forty-three of them were sent to a concentration camp, 35 of them died. By the end of 1942, a growing number of police officers joined the resistance. They assisted other members of the resistance, distributed illegal newspapers and helped people hide.

27 January 1944

Mayor Delwaide resigns

The German occupying forces claimed the Great Hall on the first floor of the town hall. They wanted to organise a farewell party here for Flemish Waffen SS volunteers. The mayor did not feel that this was the right place for such ‘political’ events. As a result, the ‘old’ aldermen resigned. Historians agreed that Delwaide used this symbolic gesture as an opportunity, as the end of the occupation approached, to ensure his record would stand up to scrutiny after the war. In the early years, collaboration with other 'illegal’ matters was much less of a problem. VNV alderman Jan Timmermans took his place.

6 June 1944

D-day

Allied troops (American, British and Canadian troops, with the support of smaller Belgian, French, Dutch, Polish and Norwegian units) land on the beaches in Normandy (France).

August 1944

The Koloniale Hogeschool as the stronghold of the resistance

In August 1944, Norbert Laude coordinated various units of the resistance, including among others the Secret Army, from the Colonial College. They were very active, publishing resistance newspapers, gathering information, helping people hide... By August, the Germans realised they were operating out of the Colonial College. They arrest Norbert Laude and several of his helpers. They tortured Laude in hopes of getting information from him. They city was liberated just in time. He escaped his own execution by the skin of his teeth.

1 September 1944

The advance of the Allied forces

Allied troops continued to advance in France. They arrived at the Belgian border around 1 September.

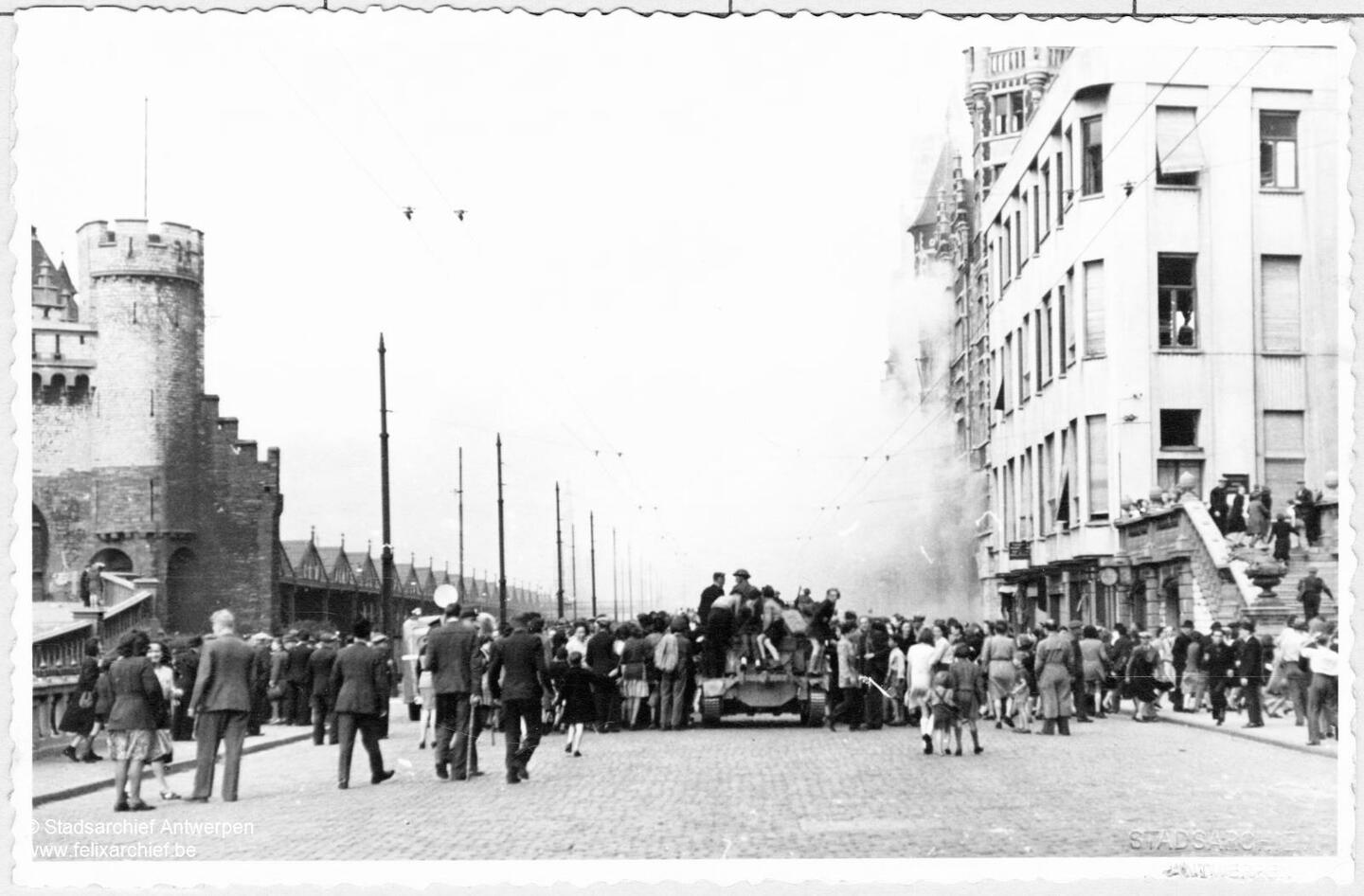

4 September 1944

The liberation of the city of Antwerp

With the help of the resistance, British tanks succeeded in pushing through to the city of Antwerp, via Boom, crossing the River Rupel and the canal at Willebroek. The assistance of the former engineer and resistance man Robert Vekemans proved pivotal for the British troops. He knew where the Germans had laid bombs under the bridges, and where they hadn’t. The British were now able to attack the Germans from behind. They gained a lot of precious time as a result.

4 September 1944

Finally!

That day British tanks rolled through the streets, liberating Antwerp The people were beside themselves with excitement and turned out onto the streets. But the German soldiers still held positions in the city, resulting in armed struggles. There were skirmishes near the bunker of the German command in the city’s park and at the Feldkommandantur in Meir. A violent battle ensued around Luchtbal, Merksem and the port.

4-5 September 1944

Repression by the population

In Antwerp, a first ‘wave’ of public anger was directed at those places in the liberated city that had come to symbolise the presence of the occupying forces. The people looted German food and other supplies. But they also targetted the buildings and property of organisations and people who collaborated with the Germans. The party offices of the VNV and DeVlag were pillaged. Several households were ransacked and possessions smashed on the streets. The same fate befell the collaborators, or in any event the people who were alleged to have collaborated. They were taken from their houses and brought to police stations, prisons and other gathering places. There was lots of shouting. People were often treated very roughly.

12 September 1944

The mayor returns

Camille Huysmans arrived in the city, after having left for the UK in the early days of the war. The municipal councils were reconvened after many years of inactivity during the war.

4 - 7 October 1944

Canadian army units liberate the northern districts

October 1944 - March 1945

Not free of war

While Antwerp was no longer occupied, the war was from over. On the contrary even. Hitler ordered the bombardment of Antwerp with V1 flying bombs and V2 rockets. The idea was to prevent the Allies from capturing the port intact and supplying their troops on the front lines. In the following months, thousands of civilians fled the city, to the country or the coast.

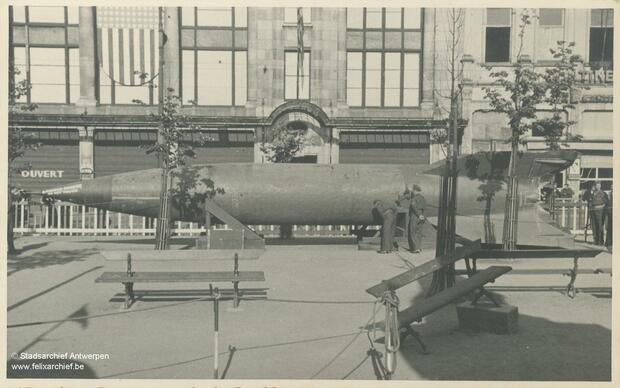

13 October 1944

The first flying bomb is dropped on Antwerp

That day the Germans dropped the first of many V rockets on the centre of Antwerp. At 9.45 exactly, in Schildersstraat, near the Museum of Fine Arts. 32 fatalities and 46 people injured. The devastation was terrible. And thus began a period of six months of constant terror. No more sleep at night.

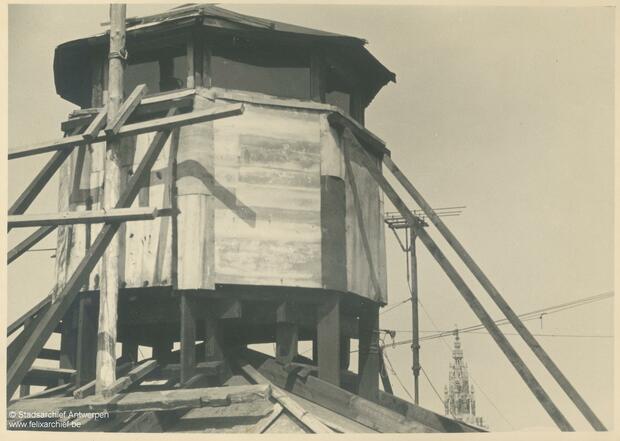

19 October 1944

Antwerp X

The Allies organised the air defence to protect the city and its surroundings. As of November, the command was in hands of the experienced American general C.H. Armstrong. He led the ‘Anti-Flying Bomb Command Antwerp X’. The Passive Air Defence also organised itself. This Antwerp organisation leapt into action every time the city was bombed, with the help of the Allies. Lookouts were installed on the Cathedral, and later also the Boerentoren building.

11 November 1944

No armistice that day

A V2 fell on Breydelstraat, killing 51 people. Two weeks later, on 27 November, a V2 fell on the busy intersection of De Keyserlei with Frankrijklei and Teniersplaats. A total of 128 civilians and 29 soldiers did not survive the impact. Another 260 people were injured.

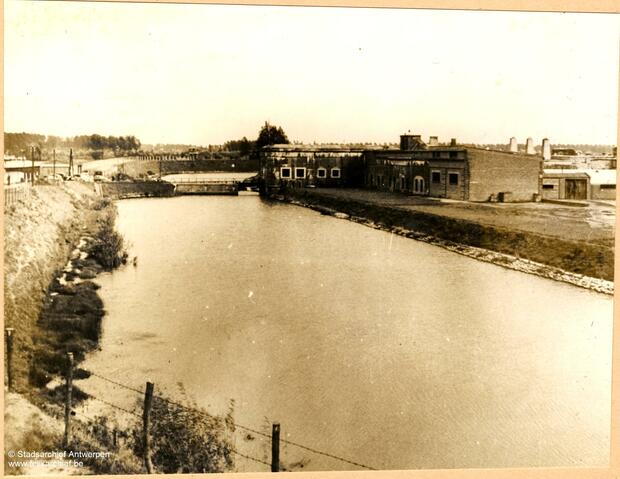

October – November 1944

Battle of the Scheldt

The port of Antwerp, the channel to it and the Scheldt estuary played a key role in the Allies’ military plans. They hoped to import troops and supplies through Antwerp, instead of through the smaller French ports. Finally, the Allied troops, led by the Canadians, managed to drive the German troops out of Zeeland-Flanders, Beveland and Walcheren. Thousands of Allied soldiers died as a result. Later the Scheldt was cleared of mines and became an Allied supply port.

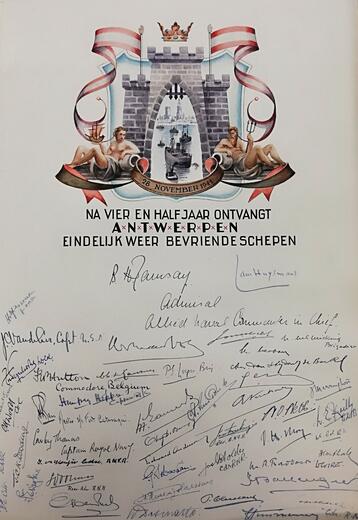

28 November 1944

The port reopens

For the first time in more than 4 years, the newly-reopened port of Antwerp receives a first ‘friendly’ ship.

16 December 1944

Beginning of the Ardennes offensive

Hitler hoped to weaken the advancing Allied troops in northern France and Belgium with this last-ditch major effort. By capturing the port of Antwerp, he hoped that he would be able to cut off the supply line for food and weaponry.

16 December 1944

V flying bomb on Cinema Rex

That day Cinema Rex in Keyserlei was showing a film called ‘The Plainsmen’, a western about Buffalo Bill. Fate struck around 3.30 pm. A German flying bomb fell on the cinema. A total of 567 people were killed. 296 soldiers and 271 civilians.

25 January 1945

End of the Ardennes offensive

The American troops managed to stand against their opponents and stop the German counteroffensive.

27 January 1945

The Soviet Red Army advances in the east.

In the meantime, the Soviet troops advanced from the east. They liberated the Auschwitz and Birkenau concentration camps among others.

March 1945

On 28 March 1945, the last flying bomb to devastate Greater-Antwerp fell on Ekeren, in Poloplein, near Hoogboom.

In that last month, the bombs made just over 200 fatalities.

October 1944 – March 1945

A deadly period

The 6-month long bombardment of Greater-Antwerp yields some staggering figures. Historians estimate that at least 2,910 to 2,957 civilians were killed in Greater-Antwerp were killed during these six months. An additional 600 Allied soldiers also died. Just over 5,200 people were injured or reported missing.

8 May 1945

V day

The end of World War II in the West Ten days after Hitler’s suicide, Germany finally capitulated. But the problems were far from over with the end of the war. Food supply continued to be a problem, as in the previous ‘liberated’ months. Many places in the city had been reduced to rubble after the bomb attacks.

April-summer 1945

The return of the Jewish survivors, political prisoners and prisoners of war

In addition to the many problems people faced with picking up their daily life after the war, they were also confronted with the devastating human suffering. In the spring of 1945, the first Jewish and other survivors of the camps returned to the city after a long journey home due to the damaged infrastructure. They arrived in Antwerp’s Central Station. As they returned, the horrors that occurred in these camps also became increasingly clear.

May – June 1945

A second wave of actions on the city’s streets

People reacted with indignation when the political prisoners and Jews returned from the camps. Their emaciated and malnourished bodies made a huge impression on people. This contributed to a second wave of actions of repression against collaborators or people who were alleged to have collaborated. Houses were smeared with graffiti. Alleged collaborators were encouraged to leave the neighbourhood, district or city. In most cases this was all that happened. There was no large-scale violence in the city of Antwerp around this time.

8 February 2026

Always free. Never for granted.

Each year we celebrate Antwerp’s liberation during World War II. The city is organising various events as part of the remembrance of the Liberation. Discover them on the 'Activities' page.

Cookies saved