‘Resistance’ and ‘collaboration’, the common denominators for the most extreme reactions to the German occupation, continue to be very sensitive and highly charged issues.

During World War II, only a limited group of people chose to consciously express their support for the politics of the Third Reich and Nazism. On the other side of the spectrum, only a minority elected to go underground and combat the same regime. Moreover, the motivation for either choice was often very different and even changed during the war in some cases.

Most people found themselves somewhere in the middle: they adapted and mainly wanted to survive.

So there were plenty of different gradations on either side. However there was a substantial difference in the risks that people took. Resistance fighters who fell into German hands paid for their actions with their lives more often than not. If the Germans did not execute them on the spot, they ended up in concentration and extermination camps. Many people were killed there or died from abuse and deprivation.

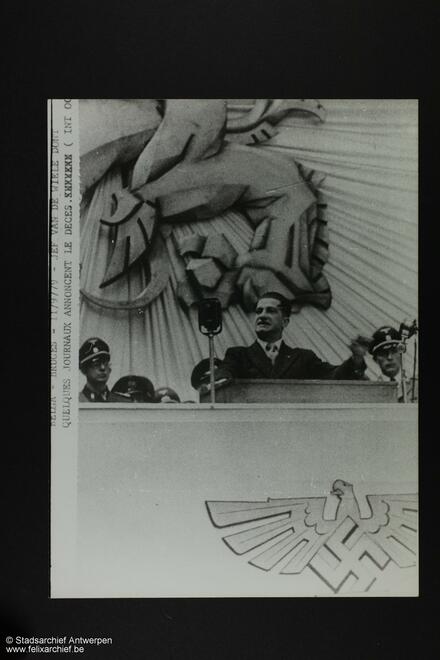

Photo left: A post-war remembrance ceremony organised by Het Geheim Leger/The Secret Army, Deurne section

Photo right: Flemish members of the SS giving the Nazi salute in Antwerp

Resistance

Who, what, why?

Not everyone who had an aversion to the German occupying regime and the collaboration, took action. This required a lot of courage and the risk of repression was substantial. At the end of 1940, in early 1941, the resistance consisted of a handful of people. From 1943 onwards, the number of resistance groups outside the large cities also increased. In the weeks and months leading up to the liberation, there were approx. 150,000 Belgian resistance fighters. Around 15,000 of them did not survive the war.

Whether people choose to make a commitment depends on several factors. They might adhere to an ideology: antifascism, an anti-German or pro-Allied attitude, a marked sense of Belgian patriotism, royalism, communism, the fight for freedom and democracy, and so on. But convictions are not the only reason. The informal pre-war networks of colleagues, family, neighbours, friends, and so on, often also play an equally important role.

The major resistance movements in Antwerp

The most important resistance movements in Antwerp were Belgisch Legioen (the Belgian Legion), better known as Geheim Leger (GL, the Secret Army) from June 1944 onwards, Nationale Koningsgezinde Beweging (NKB, the National Royalist Movement), Onafhankelijkheidsfront (OF, the Independence Front) and Witte Brigade-Fidelio (WB-F, the White Brigade-Fidelio).

These resistance movements developed during the war, with ups and downs, because the German repression was merciless. The first two Belgian patriotic organisations mainly recruited their members among former soldiers and members of the French-speaking middle class. The NKB was also a royalist movement, meaning they supported King Leopold. The OF recruited its members in very different circles. While this organisation was established by communists, it strived for a very wide popular front, and aimed to harness all antifascist powers across the various political parties. The communist party did rely on its own militants, however, for armed acts of resistance. Their group was called ‘Gewapende Partizanen’ (Armed Partisans).

The WB-F, which was founded in liberal circles by the secondary school teacher Marcel Louette, was the only group to be established in Antwerp. Its original name, the White Brigade, was extended with the name Fidelio, after Louette’s code name. This decision was made to avoid confusion after the war with ‘White Brigade’, a popular term which referred to the resistance in general. This brigade, which consisted of a handful of Louette’s colleagues and which originally published a small resistance newspaper, soon evolved into a resistance organisation, which enjoyed widespread support. They also carried out acts of sabotage, gathered intelligence, helped people go into hiding and drew up lists of ‘blacks’ (collaborators).

These resistance movements were so secretive however that some members often had no idea to which unit of the organisation they belonged. Many of the resistance fighters also knew one or two of their colleagues. This was done to prevent repression or denunciation from wiping out entire organisations.

Post-war tribute to the resistance, Marcel Louette (aka Fidelio) is sitting on a chair near the microphone.

Paper resistance: the underground press

The resistance had one clear rule: leave as few traces as possible. There was one exception to this: the underground press. The many underground pamphlets and clandestine newspapers that have been preserved attest to this. During World War II, Antwerp became the epicentre of the underground press in Flanders.

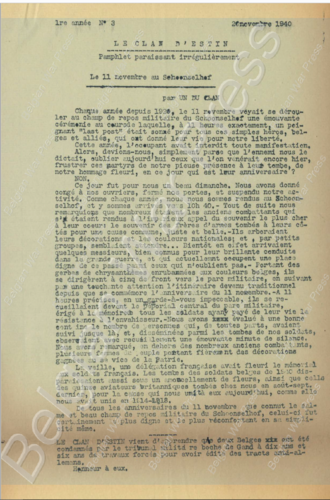

One of these publications was Le Clan d’Estin. The articles, which were written in liberal circles, conveyed a message of optimism and faith in the future. Jean Sasse, the son of the liberal alderman Eric Sasse, was one of the authors. They clandestinely printed the newspaper in Fernard Rahier’s bookshop. The issue of 20 November 1940, among others, contained a report of patriotic actions in Schoonselhof cemetery. The last edition was published in April 1941 after several people were arrested.

Gathering intelligence

One of the people to be arrested was Fernand Rahier himself, but not because of his publishing activities. He also worked for the ‘William’ intelligence service, which was led by Emmanuel Hobben. Like ‘Alex’, the other Antwerp intelligence service, which was part of the larger ‘Tégal’ network, this intelligence service attempted to get intelligence to the Allied services in London by radio or through smuggling. The ‘Alex’ service mainly consisted of former officers, who focused on military intelligence. They even succeeded in stealing the plans of the well-known Luftwaffe plane, the Focke-Wulf 190. The Germans succeeded in taking down the ‘Alex’ network, however, and also executed some of its leaders.

Le Clan D’Estin on the subject of the patriot protests in Schoonselhof - © CegeSoma/National Archives, The Belgian War Press

Armed resistance

Whereas most resistance movements in the Province of Antwerp did not use violence, they did commit acts of sabotage when necessary. They targeted the employees and buildings of the occupying regime and groups of collaborators.

Het Belgische Partizanenleger (Belgian Partisan Army), the armed branch of the communist party, was especially active. In early 1943, the Heymans group, which was named after Gustaaf Heymans, planned a bomb attack on the DeVlag headquarters in Van Eycklei. The attack was foiled, however, and Franciscus Palinkx, the bomber, was arrested by the Germans. It soon became clear that this was not his first act of sabotage. He was also implicated in an attack on a collaborator, fired several grenades at a German training ground and was arrested while attempting to attack a German military garage. This time around, he was unable to escape from the prison in Begijnenstraat. On 8 June 1943, Palinkx was led in front of a firing squad in Antwerp. Soon after, the Germans sentenced the partisans around Heymans to death by hanging. They were executed at the camp in Vught, in the Netherlands.

Sabotage

Clandestine activities also developed in Antwerp’s port, which was of huge economic and military importance to the Germans. Dock workers, the crews of tugboats, ship repairmen… from companies such as Béliard and Mercantile, which ended up under German management, organised themselves in illegal ‘Syndicale Strijd Comités’ (union militant groups). They agreed to sabotage the Germans’ production where possible. But here again, the repression was merciless. In March and July of 1942, German officers arrested Frans and Albert Adriaenssens, Jaak Pluym, Henri Hazen, Jan Van Herck, Jozef Pir, Pierre Wellekens, Petrus Vande Velde and Jozef Doms among others. They all worked at Mercantile. Often the men were sent to Breendonk, from where they were transferred to other camps where they died.

Funeral of resistance fighters after the war, which attracted a large number of mourners.

Assisting people to go into hiding

Many people also took actions or offered services that were less directly oriented against the occupying forces and their helpers. These include people who helped Jewish people or Allied airmen whose airplane had crashed, and who had to disappear underground.

From 1943 onwards, the Socrates service helped people who refused to work for the Germans and other people who were forced to go into hiding. After the enforcement of forced labour in autumn 1942, many people decided to go into hiding. From then on, they no longer had an income and lived in an illegal place of residence. Their family members also risked sanctions as a result. The people in hiding needed any support they could get. The Socrates service was an initiative of the government in exile in London, but its operations were carried out by the resistance groups.

One of the ‘strong men’ in Antwerp was Dirk Sevens, the substitute of the public prosecutor. He also actively aided Jewish people. The Germans identified this young magistrate one month before the liberation of Antwerp. Sevens was arrested and taken to the Sipo-SD headquarters, after which he was transferred to the Fort of Breendonk. The Germans tortured Sevens so badly while questioning him, that he was barely recognisable upon his arrival in Breendonk. Nonetheless he was forced to do hard labour in spite of his condition. On 9 August 1944, Sevens died after being struck repeatedly by one of the camp guards. A bust opposite the entrance to the office of the public prosecutor in the old Law Courts in Britselei, pays tribute to his resistance efforts.

Het Geheim Leger/The Secret Army, Berchem section, pays tribute to Dirk Sevens.

Youth action

A group of young Antwerpers, who were all members of the ‘Belgische Rekruten Boksers’ boxing club organised themselves rather spontaneously and separately from the larger clandestine organisations. They used BRB as a code name for their clandestine ‘Belgisch Revolutionaire Beweging’ (Belgian Revolutionary Movement). At the end of January 1942, they planned several actions in one day. They targeted a DeVlag building in Deurne and smashed a window of the VNV building in Frankrijklei. But one local policeman succeeded in arresting them and reported them to the Germans. Soon it became clear that these young men were responsible for plenty of other acts of sabotage. The Germans arrested 22 of them. Nine of them died in the camps. The others returned to Antwerp after the war.

A place of remembrance

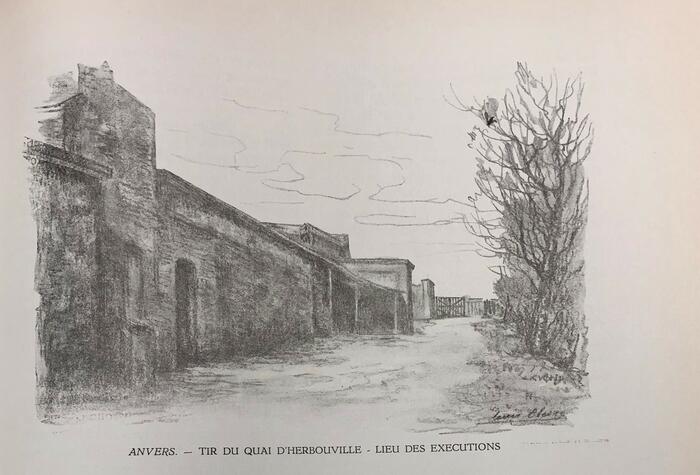

Not many people know that the Antwerp ‘Feldkommandantur 520’ executed people who were sentenced to death in D’Herbouvillekaai, in hangar 9A and on the military site in Maria-ter-Heide in Brasschaat. Historians estimate that 130 people were executed.

The place where executions took place in Antwerp, the shooting range in D’Herbouvillekaai - © Héros et Martyrs 1940-45 les fusillés, Brussels, 1945, p. 249

Collaboration

Who and why?

Collaborators actively aided the Germans, purposefully serving their interest. Historians estimate the total number of collaborators in Belgium to be circa 100,000, a small minority in other words. Not everyone who endorsed the ideas of the New Order or who had certain sympathies also proactively aided the occupying regime.

The collaboration has many faces and gradations. Here too, the underlying motives were very different. Some chose to collaborate because of personal ambitions or political aspirations, ideology, a sense of adventure, idealism, or because they thought that they could profit from it. The penal code distinguishes four forms: denunciation, economic, political and military collaboration.

Show of strength on the street

The largest collaborating party, the ‘Vlaams Nationaal Verbond’ (VNV, Flemish National Alliance), as well as other movement such as the Greater-German ‘Duitsch-Vlaamsche Arbeidsgemeenschap’ (DeVlag, Dutch-Flemish Labour Community) and SS-Vlaanderen had a strong presence in Antwerp. One of the figureheads of the anti-Belgian collaboration was August Borms, who lived in Merksem.

The collaborating groups regularly marched through the most important streets of Antwerp, in a big show of strength. They waved flags, gave the Nazi salute, held speeches, and marched through the streets in uniform, in orderly formation. The many propaganda images that have been preserved show how these parades gathered a lot of supporters and huge crowds of onlookers, especially in the early years of the war.

Denunciation

Other collaborators operated must more clandestinely. Those who denounced others often did this anonymously. The reasons for these denunciations were often very diverse. Revenge as part of a banal conflict between neighbours, for example. But also barely-veiled anti-Semitism, which led to the arrest of many Jews who had gone in hiding. The large group in between these two extremes mainly denounced others in support of the occupation policy and out of ideological conviction.

In addition to these snitches, there were also plenty of ‘professional’ informants in Antwerp. They often had connections with the Belgian and German police forces. They supplied all the information they gathered about resistance fighters, communists, Jewish people and other people in hiding to the German police.

Political collaboration

From the outset, political movements such as VNV, REX and DeVlag supported the German policy in occupied Belgium. They felt that the German occupation was the best guarantee to achieve their own political plans.

As the war progressed, the rivalry between these organisations grew. Despite an important Greater-Dutch movement, the majority of the VNV members hoped that Flanders would become independent in a Europe that was dominated by a national-socialist Germany. The leader of the VNV in Antwerp was Jan Timmermans. He was a city councillor and was even appointed as alderman and mayor during the war.

Other organisations such as DeVlag and SS-Vlaanderen opted for a radical Greater-German course and hoped that Flanders would be integrated in a Greater Germanic Empire. One of the leaders of the latter organisation was also an Antwerper, the lawyer René Lagrou who was a staunch Nazi.

Photo left: Pre-war meeting in Antwerp of ‘Vlaams Nationaal Verbond’, a pro-German political party.

Photo centre: The crowd salutes a group of men who are leaving from Antwerp for the Eastern Front.

Photo right: Jef Van De Wiele from Deurne, a leader of DeVlag.

Military collaboration

In Antwerp too, many men chose to take up arms for Hitler. The best-known examples are the so-called oostfronters, who assisted the German troops in the East. Movements such as the VNV and DeVlag recruited them, to join the Flemish Legion and the Waffen-SS.

These volunteers were publicly cheered when they left from Antwerp’s Central Station by train. This public show of strength was designed to encourage others to follow their example.

These men had very diverse motivations: belief in Nazi Socialism and the Third Reich, anti-communism, a sense of adventure, leaving behind problems at home, financial considerations, avoiding forced labour and so on.

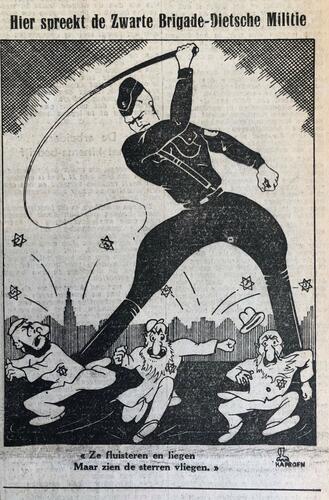

Other military auxiliary troops such as Dietsche Militie-Zwarte Brigade (German Militia-Black Brigade), Vlaamse Wacht (Flemish Guard) and Fabriekswacht (Factory Guard) also operated in occupied Belgium. The former were the storm troops of the VNV. The latter carried out guard missions for the German field army and the Luftwaffe (Deurne airport) and helped track down resistance fighters.

Waving goodbye to men off to the Eastern Front

Economic collaboration

The mindset of many small and large enterprises that continued to do business during the occupation is more difficult to assess. Some companies found themselves under German management and had no choice but to produce for them, such as the Antwerp plants of Ford and General Motors and other companies in the port.

But there were definitely cases of business owners who purposefully chose to collaborate, purely to make a profit, out of opportunism, to serve their own interests, and in some cases because of their political convictions. After the war, they risked being sentenced for economic collaboration.

The attitude of the majority of business owners was much more complex however, and was founded on the Galopin doctrine. This doctrine was the result of negotiations between leading Belgian entrepreneurs. Some business owners were not interested in closing down or hoped to continue to employ their workers. Others hoped to avoid that their plant would fall in German hands.

Cultural collaboration

The German military authorities wanted cultural life to continue, under the occupation. That is why the Germans went in search of Belgians who were prepared to collaborate with them. Many collaborators held prominent positions in the various cultural services that were established at the start of the war. One of them was Jef Van de Wiele, a radical national-socialist who lived in Deurne. He was the leader of DeVlag and was appointed as secretary of the Vlaamsche Kultuurraad (Flemish Culture Council).

Very few artists openly expressed their unconditional support of the Third Reich in their work. One author who did choose sides was the Antwerp-based Flemish nationalist poet and author Blanka Gijselen. She published poetry and worked for several collaborating newspapers such as Volk en Staat and De Vlag.

Often artists (authors, draughtsman, painters…) were given the choice to accept certain offers or commissions. One such artist was the young Antwerp comic artist Willy Vandersteen, who later became famous as the creator of Bob and Bobette.

A lot of uncertainty prevailed for many years about his wartime activities. There can be no confusion however about the work he did for Nationale Landbouw en Voedselcorporatie (the National Agriculture and Food Corporation) and the Antwerp branch of Winterhulp. Recent research has shown that he also created less innocuous drawings for the collaboration newspaper Volk en Staat. He drew several anti-Semitic cartoons, using the pseudonym ‘Kaproen’, and other drawings that condoned the collaboration.

Willy Vandersteen drew a number of cartoons for the pro-German newspaper Volk en Staat