The Nazis who came to power in Germany in the early 1930s were openly anti-Semitic and took many anti-Jewish measures. After the German army occupied Belgium in the spring of 1940, it did not take long before the Germans proclaimed their first anti-Jewish decrees. Registration, identification, bans and stigmatising measures, such as the wearing of the yellow Star of David, were enacted in rapid succession. Deportation was the next step, after economic exclusion. Many thousands of Antwerp Jews did not survive the war. The Germans transferred them to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. Antwerp’s police force and city council played a special role in this. They actively assisted the Germans during several large-scale raids in the summer and autumn of 1942. Those Jews that did escape the horror lived in a climate of constant fear. Some went into hiding on time, others succeeded in leaving the country and yet others joined the resistance. In some cases, they were able to rely on the assistance and solidarity of neighbours, friends and colleagues.

Antwerp Jews before the war

Antwerp has had a Jewish community since time immemorial. Their numbers increased substantially from the end of the 19th century onwards due to migration from Eastern Europe. This trend continued during the interbellum period. At the end of the 1930s, Antwerp was the preferred destination for many of the Jews who chose to flee the rampant anti-Semitism in Nazi Germany. Historians estimate that there were about 35,000 Jews in the city on the eve of World War II. Many of them were foreigners, who did not have Belgian nationality.

There was and is no such thing as one single Jewish community in Antwerp. The Jews in Antwerp spoke different languages, and had different nationalities. But the way in which they practiced their religion and culture was also different. They did join forces, however, to establish ‘De Centrale’, a social aid organisation. Just before the war Antwerp had 3 synagogues and 8 places of prayer. The orthodox Jews especially had a strong presence in Antwerp.

Concentration

As is still the case today, Antwerp’s Jews tended to live very close to each other during World War II. The streets around the city’s Central Station were commonly known as the ‘Jewish neighbourhood’ (6th and 7th district). The majority of the Jewish community outside of Antwerp’s city centre lived in Berchem or Borgerhout. The concentration was also apparent on the professional level. Many Jews worked in the diamond, textile or furniture industry.

Encroaching anti-Semitism

As was the case elsewhere in Europe during the 1930s, anti-Semitism became rampant in Belgium. The sentiment was not as strong as in Nazi Germany though, where the ‘Kristallnacht’ took place in November 1938, resulting in large-scale public violence against Jews and Jewish places. In Belgium, certain Catholic, Belgian-nationalist and Flemish-nationalist groups tended to support anti-Semitic ideas. The Flemish Conference of the Bar of Antwerp (a group of pro-Flemish Antwerp lawyers) decided to disbar Jewish lawyers from the bar association as early as 1938-1939. Two years later, the Antwerp Executive of the Antwerp Bar disbarred another 17 Jewish colleagues and trainees.

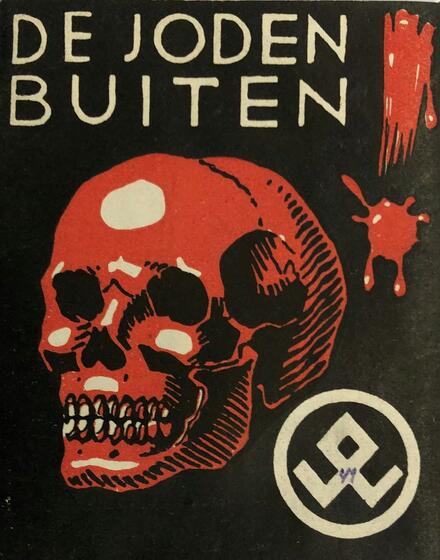

The anti-Jewish discourse soon spread through various magazines and political groups. The best-known example was an organisation called ‘Volksverwering’, which was led by the lawyer René Lambrichts.

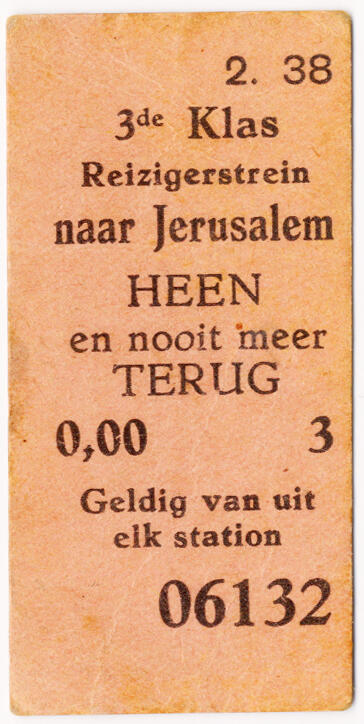

Photo left: Anti-Semitic train tickets are stuffed in Jewish people’s letterboxes before the war - © Collection of Antwerp City Archives

Photo centre: The Jews react with their own train ticket - © Collection of the Antwerp City Archives

Photo right Volksverwering is the instigator of these actions - © Collection of the Antwerp City Archives

Anti-Jewish decrees and measures

In October 1940, the German military regime published the first anti-Jewish measures. The 18th and last anti-Jewish decree dates from the end of September 1942. There are several phases to be distinguished in these two years. The registration came first, followed by the exclusion from economic and public life. And lastly, Jews were isolated, counted and even ‘marked’. The deportation was the final chapter.

A short overview of the anti-Jewish decrees and some other measures proves how systematic the Germans went about their job:

- 23 October 1940

A ban on ritual slaughtering takes effect - 28 October 1940

- Jews who left the country during the invasion were banned from returning to Belgium.

- The authorities determined who was Jewish.

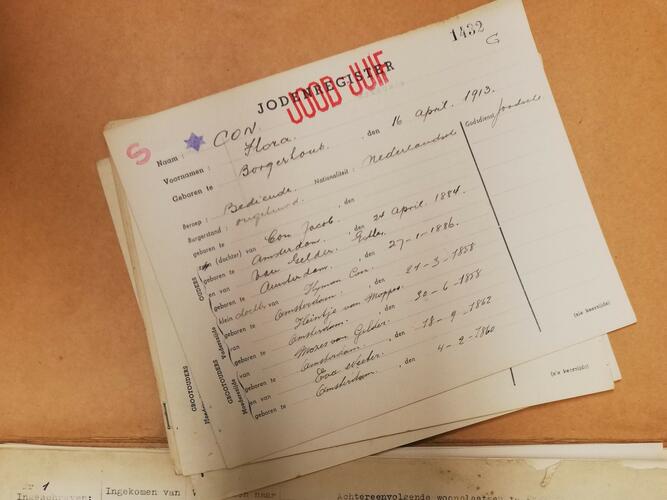

- All Jews over the age of 15 years were registered in a special Jew Register.

- Jewish businesses were forced to declare their assets.

- Jewish restaurants were forced to put up a sign reading ‘Joodsche onderneming’ (Jewish business).

- Jewish employees were dismissed from public office (education, law, journalists, etc.).

- December 1940 – February 1941:

3,000 Antwerp Jews and other foreigners were transferred to Limburg, where they were forced to work for the Germans. - 31 May 1941

From now on Jews were forced to declare their intangible assets, accounts and other securities to German services. Jewish businesses were placed under German management. - 29 July1941

Municipalities were forced to stamp ‘Jew/Jood/Juif’ on identity cards. - 29 August 1941

Jews were banned from leaving their house between 8 pm and 7 am. They could only move to Brussels, Antwerp, Liège or Charleroi. - 25 November 1941

At the request of the German authorities, the Jewish Federation was founded in Belgium. All Jews living in Belgium were forced to join the federation. The daily management was in hands of prominent Jews. The federation’s activities were overseen by the German military authorities and the Ministry of the Interior. This was just one option for the Germans to find out where Jews lived in Antwerp. It also facilitated their arrest later. - 01 December 1941

Jewish children were no longer admitted to non-Jewish schools. - 17 January 1942

Jews could not leave the Belgian territory without German permission. - 11 March 1942

Jews were employed by the German authorities. - March-April 1942

A third Jewish census was organised in preparation of the deportations. - 22 April 1942

The assets of Jews living in Belgium, who held German nationality, was confiscated. - March – April 1942

Everyone was forced to declare rough and polished diamonds to the German authorities ‘Diamond Control’. Companies that were affiliated with this were forced to stop their activities. - 08 May 1942

The rights of Jews on the labour market were completely scaled back. - 01 June 1942

Jews were banned from practicing medicine. - 01 June 1942

Jews were forced to wear the Star of David. - Spring of 1942

Non-Belgian Jews were forced to work for the German authorities. The occupying forces employed 1,500 Antwerp Jews in northern France in just four months’ time. - Mid-July 1942

Jews were requisitioned for the ‘Arbeitseinsatz’ and were informed that they had to report to the Dossin Barracks. - 22 and 23 July 1942

Start of the raids in Antwerp.

The German military authorities counted on the collaboration of the municipal councils for the execution of some of these decrees. This was not seen as a problem in Antwerp. Historical research has shown that the city council, the administration, and the local police force adopted a flexible and accommodating attitude. They assisted the German authorities whenever it was expected of them. This happened during the raids, for the drawing up of the Jew Register, the issuing of the invitation to report for compulsory employment, the ‘Jew’ stamp on ID cards and the escorting of Jews to the station for forced labour in Limburg and northern France.

Registration in the Register of Jews - © Collection of the Antwerp City Archives

Violence in public space

In the summer of 1942, the world of Jews was very limited in Antwerp. This caused some people to leave the country. Others did not have the means for this. They adopted an expectant attitude and hoped that things would soon improve. In the meantime, the Jewish population was increasingly often confronted with physical violence.

The Antwerp police reports contain several examples of Jews who were confronted with harassment, theft, robbery, threats and increasingly often, violence. The best-known example of public violence against Jewish inhabitants took place on Easter Monday 1941 in the ‘Jewish’ sixth district, the neighbourhood around Central Station. After the screening of the propaganda film Der Ewige Jude, which was organised by the radical anti-Jewish Volksverwering movement, the crowd felt compelled to take action. Things soon got out of control. 200 Antwerpers and Germans destroyed a rabbi’s house and set fire to the synagogues in Van Den Nestlei and Oostenstraat. They destroyed everything and prevented the firemen from extinguishing the fires. Plenty of windows were smashed in the Jewish neighbourhood that evening.

Violence against Jews on Easter Monday 1941 © Collection SegeSoma/National Archives

The raids in the summer of 1942

During World War II, a total of 28 transports left from Belgium. Almost all of them were headed for the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. They had a total of 25,250 Jews and 352 gypsies on board. Only 1,251 of them would live to tell the tale. These transports left from the Dossin barracks in Mechelen. Seventeen of these 28 transports took place in a short period, between 4 August and 31 October 1942. By then, approximately 10,000 Jews had already been rounded up during the raids. Only 55% of the Jews who were registered in Belgium survived the war.

Multiple raids took place in Antwerp in the summer of 1942. Depending on which counting method is used, historians distinguish five different raids. More than anywhere else in Belgium, the ruling elite (mayor Delwaide, commissioner De Potter and public prosecutor Edouard Baers) adopted a compliant attitude, with the local police assisting the Germans.

Five large-scale raids

The first raids took place on 22 and 23 July 1942. German officers of the Sicherheitspolizei rounded up a few hundred Jews who arrived in Central Station from Brussels on these dates. A similar raid was conducted in nearby Pelikaanstraat.

The second and third raids took place on 13, 14 and 15 August. In the night of 13 and 14 August, German officers arrested 206 Jews, including 53 children. Most were Eastern European Jews. One day later, they organised another large-scale raid, rounding up more Jews. This was also the first time that the Antwerp local police openly collaborated. Antwerp officers helped fence off the streets and escorted the Jews to the trucks. German officers entered homes, brutally dragging out the occupants. The raid lasted all night. An estimated 845 Jews were taken away. Mayor Delwaide and public prosecutor Baers remained silent and did not react to the events. However, they knew about the events because of the official police reports.

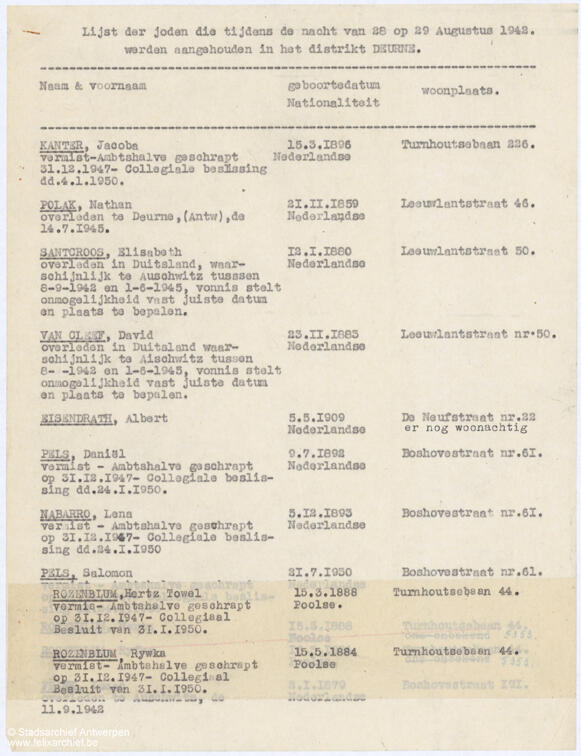

The fourth raid took place in the night of 28 August. Originally it was scheduled to take place the previous day, on the 27th, but the Germans shelved the idea at the last minute. Apparently some policemen alerted the Jews. The Antwerp local police force was given a more active role, in revenge for the sabotage of the previous day. They received orders to arrest 1,100 Jews themselves. Commissioner De Potter did not flinch when he told his policemen to carry out the orders. Some refused to collaborate, others turned a blind eye here and there. Where necessary, reinforcements were called in from other units. Every police district was ordered to arrest 250 Jews. The arrested Jews were rounded up in schools in Grote Hondstraat (Zurbenborg) and Vinçottestraat (Borgerhout) as well as in Cinema Plaza (Gallifortlei, Deurne). The next morning they were transferred to the Dossin Barracks in trucks. Again, Antwerp’s local authorities did not budge.

The fifth large-scale raid took place on 11 and 12 September. That day, the Germans did not rely on the collaboration of Antwerp’s police force that day. Some policemen assisted their German colleagues during these raids. They rounded up the Jews in various locations throughout the city. They were plucked off the street here and there. This raid was clearly less systematic and more random. That did not make it any less efficient. The Germans arrested 679 Jews on that day.

Photo left: Dossin Barracks, summer 1942

Photo right: List of Jews arrested in Deurne

What happened after 1942

In the days, weeks and months after the raids, the Germans continued their operations. As of September 1942, they no longer relied on the active collaboration of Antwerp’s local police force. They adapted their tactics, choosing to solely rely on German policemen and their henchmen.

To find the many Jews who had gone into hiding, German officers raided places where ration cards (the cards that every Antwerper needed for food) were distributed, with the help of Antwerp Jew hunters. There were raids in the period from 22 until 25 September 1942 in the Antwerp Festival Hall in Meir, in the town hall in Borgerhout and in the secondary school (atheneum) in Deurne. The ration cards helped them find out where Jews had gone in hiding. A total of 760 Jews ended up in the Dossin Barracks as a result of these raids. By the end of 1942, approximately 4,000 Antwerp Jews had been rounded up.

Even later, from early 1943 onwards, the Germans opted for small-scale raids and arrests. They still relied on the loyal collaboration of a group of local Antwerp employees, informers and snitches. The latter proved especially important when searching for Jews in hiding. A few thousand Jews were arrested during the period after the big raids of 1942.

Theft, extortion and vacant houses

Jews who were arrested had to leave everything behind. In some cases, they were allowed to take some personal belongings, clothes or food with them. The same applied to Jews who went into hiding or fled. Although they sometimes had more time to prepare their journey, they were not able to do much else. The houses, apartments and studios of Jews remained vacant. Some landlords, tenants, neighbours, or ‘concierges’ stole their belongings. The Jew hunters and German policemen did exactly the same. Other Antwerpers also took furniture with them or even moved into the vacant houses themselves. Soon these break-ins became a real problem.

Aktion Iltis

On 3 and 4 September 1943, the German police organised a last big raid in Antwerp, as part of the so-called ‘Aktion Iltis’. In contrast with previous Jewish raids, the German police and their henchmen now targeted Belgian Jews. Another 432 Jews were arrested in Greater-Antwerp. After this raid, the Germans officially declared Antwerp to be ‘Judenrein’.

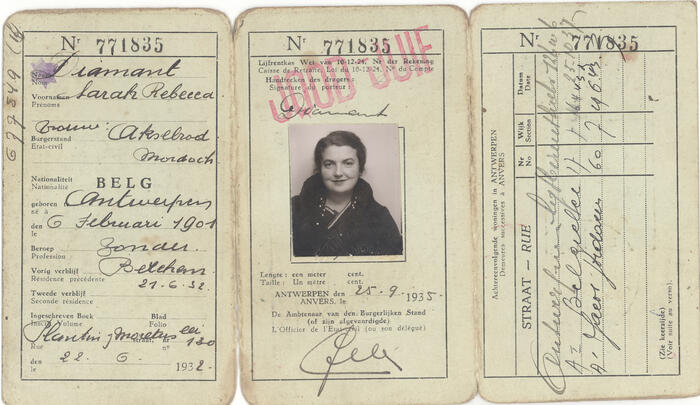

Sara Rebecca Diamant Akselrode from Antwerp was one of the victims of the Iltis raid - © Dossin Barracks

De Antwerp situation in context

Historians who are conducted research into the persecution of Jews in Belgium often refer to the ‘Antwerp specificity’. This means that the Jewish population in Antwerp ran a higher risk of deportation than elsewhere in Belgium (Brussels, Liège…) for a variety of reasons. The exact percentage of Antwerp Jews who were transported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp is very difficult to calculate. Research is still ongoing. The historian Lieven Saerens, who has performed in-depth research into the Antwerp specificity, says the figure is in the range of 65 to 68%. Current research, which is conducted by the Kazerne Dossin Museum, confirms that the Antwerp deportation figure is higher than the national average of 45%. Their provisional research results however indicate that the figure is less than 65%. Saerens’s calculations suggest that approximately 10,000 Jews from Antwerp did not survive the war.

RESPONSE TO THE PERSECUTION

The German persecution policy forced many Jews to flee or go into hiding, putting them in a situation where they were entirely dependent on others for food, housing and their survival. An estimated 15,000 Jews in Belgium were able to flee or go into hiding after the summer of 1942.

In the summer of 1942, the help of bystanders was limited, and mainly consisted of unstructured and usually individual initiatives of neighbours, acquaintances or friends. They often did this out of solidarity or charity. They offered accommodation, helped Jews go into hiding or free or took care of their children. Others tried to help with food or cash.

In view of the speed of the raids in the summer of 1942, Belgian assistance came too late for many Jews. The majority of the action was taken after the raids, while the anti-German sentiment grew following the introduction of forced labour (6 October 1942) and some major German military defeats later that year and in early 1943.

Gradually the growing number of aid incentives became embedded in existing resistance movements. Onafhankelijkheidsfront (OF, the Independence Front) was the most active organisation. It recruited its members in left-wing and antifascist circles and often worked with Jewish resistance fighters. The OF and other networks supplied forged documents to Jews and tried to smuggle Jewish children out of Antwerp to more remote villages in Kempen/Campine, Flemish Brabant and the Ardennes. Catholics and other religious people also attempted to hide Jewish children in their buildings.

Jewish resistance

Antwerp’s Jews did not passively undergo this situation. Instead they tried to organise themselves, but this proved quite difficult. Many Jews had already been arrested. Communist Jews were the first to take action, establishing a resistance movement called ‘het Joodsch Verdedigingscomiteit’ (The Jewish Defence Committee). The committee was established in the summer of 1942 and was later integrated in Onafhankelijkheidsfront. It was a group of Jews from various backgrounds, which succeeded in saving thousands of Jews all over Belgium. The committee had a strong presence in Brussels and Charleroi initially. The first division in Antwerp was only founded at the end of 1943. They arranged for assistance, places where people could hide, food and cash. The protagonists of this Jewish resistance group in Antwerp were Abraham Manaster, Josef Sterngold and Leopold Flam.

The Jewish resistance fighter Josef Sterngold in 1943 - © Antwerp City Archives

The return after the war

The German persecution policy had a great impact on Antwerp’s Jews. The majority did not survive the war. Those who did survive the camps returned broken, with plenty of physical and mental consequences. The human suffering was overwhelming. Everyone had family members, friends or acquaintances who died in Auschwitz-Birkenau. They had no idea about what had happened to their children and grandchildren. In the first days, weeks and months after the liberation, information was scarce.

The Jewish community tried to organise itself, establishing the ‘Comité ter Verdediging van de Joodse Belangen’ (Committee for the Defence of Jewish Interests). This committee tried to gather information, arrange accommodation and offer aid and assistance to those who returned. But they faced plenty of practical problems. Houses, apartments and property had often been confiscated by other tenants or residents. Furniture had disappeared. Cash and other valuable belongings had mysteriously disappeared. The committee therefore lobbied the government for beneficial treatment and facilities.

In spite of all this, Jewish life in Antwerp resumed gradually. Many ‘new’ Jews also chose to move to the city after the war.

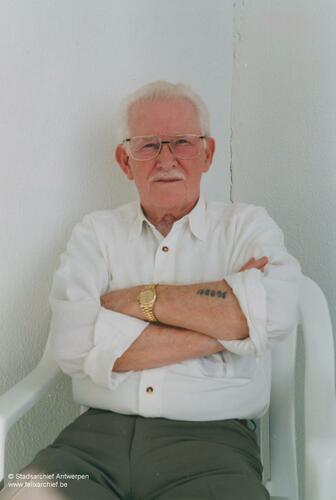

The Dutch Jew Emile Vos was arrested in the night of 28 August 1942. He survived the camps.