A good collaboration with Antwerp’s city council and its powerful port was a priority for the German occupying forces. And mayor Leo Delwaide did not oppose this. The Germans did not have to appoint a collaborating ‘wartime mayor’ in Antwerp. As was the case in other cities, Antwerp’s city council complied with the demands of the Germans. The town hall carried out the German orders without too much opposition. The lowest point was the city council’s active contribution to the raids on Jews in the summer of 1942. Later, when the tide was turning for the Germans, Antwerp’s mayor and aldermen adopted a more cautious approach. German demands increasingly met with protest. From then on, they increasingly based their decisions on an Allied victory.

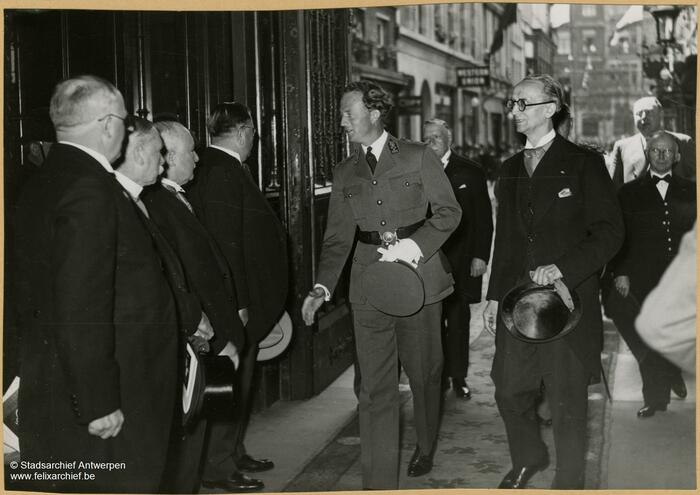

The socialist mayor Camille Huysmans shakes the hand of King Leopold III in 1938.

Crisis

At the start of the war, the socialist mayor Camille Huysmans decided to flee Antwerp. This was a difficult decision as mayors are expected to remain in their post during the war. As an MP and a notorious opponent of the Nazi regime, Huysmans chose to follow the Belgian government to France. This was soon followed by reproaches, that he had abandoned his fellow citizens to an uncertain fate. He would remain in London for the duration of the war. After Huysmans’s departure, the catholic alderman for the port, Leo Delwaide, took over his post.

Huysmans was not the only one to have fled. The local government was completely disrupted. Many of the local officials, public servants and police officers left their post. Some joined the Belgian army, others fled the German army and the war. The latter risked being sanctioned by the city council.

Recovery

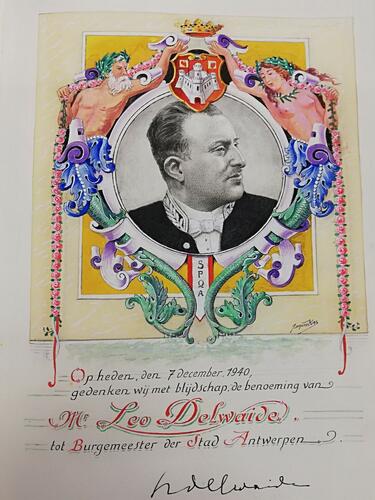

After Huysmans’s departure, the catholic alderman for the port, Leo Delwaide, was appointed as mayor. In the meantime, the city council tried to cope with the first difficulties resulting from the German occupation: billeting (German soldiers who were lodged in the homes of civilians), the confiscation of property, refugees and food shortages.

The German supremacy in 1940 was overwhelming. Soon everyone felt as if Germany had won the war. Antwerp’s political elite was inclined to agree. This gave rise to a context of practical collaboration. The first contacts between the Germans and the city council went well.

Leo Delwaide is appointed as the new mayor - © Antwerp City Archives

Governments under the occupation

Belgium was controlled by a German military occupation authority. From then on, the international law of war was enforced (Hague Conventions). This stated that local governments and the occupying forces had to collaborate, in the interest of the civilian population, to maintain order and keep the country running.

In spite of this basic principle, the instructions for the local governments were very vague. Nobody stipulated the extent of this ‘collaboration’. Officials could only protest or resign if German orders contravened national interests. In case of doubt, officials were expected to request advice from their superiors in Brussels. It soon became clear that these guidelines were almost meaningless in practice.

Historians describe the course that a large part of Belgium’s political elite chose to follow as ‘accommodation’ and ‘the lesser evil’. This means that they recognised the dominance of the Germans and adapted to the orders and situation for four years. They complied and collaborated to prevent worse things from happening. By following orders, they hoped to maintain control and prevent the Germans from doing worse.

In Antwerp, Delwaide and his colleagues also opted in favour of a policy of far-reaching collaboration with the Germans. There are a number of explanations for this:

1) The good contacts with Stadtkommissar Walter Delius and Feldkommandantur 520.

2) By remaining in their post, they prevented the pro-German collaborators from taking over.

3) Part of Antwerp’s political elite and the city’s administration espoused the ideas of the New Order to a certain extent.

They were no longer in favour of the pre-war parliamentary democracy with its controlled decisiveness. Instead they argued in favour of a more authoritarian system with strong leaders.

The socialist mayor Camille Huysmans decided to flee Antwerp at the start of the war”

Greater-Antwerp

In early 1942, this far-reaching collaboration finally started to bear fruit. The Germans ordered a merger, for purposes of efficiency. The outcome was the creation of ‘Greater-Antwerp’, a new metropolis, with a population of 530,000. The driving force behind this merger was Stadtkommissar Delius. This reform, with the support of Mayor Delwaide and some of the Antwerp aldermen (for the port) was illegal and even undemocratic.

The Germans saw this as a way of increasing their control over Antwerp and the surrounding region. The various police forces were now supervised by Delwaide and Commissioner Jozef De Potter. The power was thus in hands of a smaller group of people, and the control over policy slowly dismantled. The city councils no longer convened. The municipalities of Ekeren, Berchem, Mortsel, Merksem, Borgerhout, Hoboken, Deurne, and Wilrijk ceased to exist.

A power grab by means of collaboration

The creation of Greater-Antwerp gave rise to a reorganisation of the local government. Delwaide retained the city council’s trust, and stayed on as mayor. The mayors of Borgerhout, Merksem and Deurne were all appointed to the city council, along with some aldermen, who had been elected before the war. But several, infamous, pro-German collaborators, including Robert Van Roosbroeck (DeVlag and Algemeene SS-Vlaanderen), Odiel Daem (Rex), Piet Boeynaems (VNV), Berten Vallaeys (VNV) en Jan Timmermans (VNV) were also appointed as aldermen. As such, they also controlled the city and owed their appointment to the occupying forces. Although they were not in the majority, they were able to exert pressure on Delwaide.

Photo left: 'Het Vrije woord’ © CegeSoma/Rijksarchief

Photo right: Two of the new aldermen: Rob Van Roosbroeck (left) en Jan Timmermans (middle), Cyriel Verschaeve (right) © Collectie AMVC-Letterenhuis

The persecution of the Jews

The Jewish residents of Antwerp would feel the consequences of this far-reaching accommodation policy the most. The local government of Antwerp suddenly found themselves in troubled waters when they decided to comply with the execution of these German anti-Jewish measures. This included registering Jewish residents of the city in a register of Jews, collaborating with the employment of Jews in Limburg, checking that restaurants and bars featured Jewish signs on their façade, stamping passports with ‘Jew’, distributing the ‘star’ that Jews were forced to wear and finally the Einstatzbefehle for the compulsory labour of Jews.

In the summer of 1942, this policy sank to its lowest point. The Germans carried out various raids, on the Jewish population, in which Antwerp’s police force played an active role. Mayor Delwaide, Commissioner De Potter and public prosecutor Baers did not react.

But things did not end there. Delwaide had several policemen, who sympathised with the New Order, transferred to the sixth ‘Jewish’ district. Policemen who refused to collaborate risked being sanctioned by the mayor. In recent years, several historians have stressed Mayor Delwaide’s role and political responsibility in these events. In their view, this is also one of the reasons why the number of Jewish deportees is higher than in Liège or Brussels for example.

Chief commissioner Jozef De Potter

1942-1943: the turning point

At the end of 1942 and in early 1943, Antwerp’s mayor and aldermen adopted a different attitude. There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, the fact that the Germans were defeated at El Alamein and Stalingrad. And secondly, the introduction of compulsory labour in October 1942.

The compulsory labour especially caused a huge commotion, with people protesting and resisting this measure in occupied Belgium and Antwerp. The first official to change his mind was public prosecutor Baerts. A few months after the raids, he informed Delwaide and De Potter that the local police forces should refrain from assisting the occupying forces with their arrests. These instructions came as a big shock to the police. This was the first time that they were given this instruction. Even later, in February 1943, Baers expressly forbade the police from arresting men who refused to perform forced labour.

Soon the change in policy was obvious to everyone. In January 1943, the city council refused to assist the Germans, when the Werbestelle contacted the municipal services, requesting lists with names of city officials. The Werbestelle officials had no choice but to start going through the civil registry themselves.

The city did not just protest against the fact that the Germans wanted Antwerpers to go work in Germany. At the end of November 1942, and later, refused large-scale confiscations of equipment (cranes, machinery…) in the port on several occasions.

From 1943 onw ards, Delwaide attempted to symbolically distance himself from the occupying forces and collaboration. Shortly after the attack on Mortsel, he refused to receive members of the ‘Vlaamsch Legioen’, who raised money for the victims, at city hall. A number of members of the Waffen-SS then took it upon themselves to invade Delwaide’s house and destroy furniture as a reprisal.

A new wartime mayor for Antwerp: Jan Timmermans

At the end of January 1944, a new mayor was appointed in Antwerp. Jan Timmermans, who was an Antwerp lawyer and a member of the VNV, finally got his chance. He had sought to become the mayor of the city since the foundation of Greater-Antwerp. He had to accept the position of alderman for the port in anticipation of this opportunity.

Why was he successful this time around?

On 27 January 1944, Leo Delwaide and the other aldermen who represented the “Old Order” resigned. The Waffen-SS had already been looking forward for quite some time for an opportunity to organise a farewell ceremony in the town hall for Flemish SS volunteers who were about to depart for the Eastern Front. At this late stage in the war, Delwaide objected on principle. But his decision was also motivated by other factors. The mayor wanted to use this opportunity to clearly show to everyone on which side he was. Timmermans, meanwhile, saw this as an occasion to eliminate Delwaide as mayor.

Timmermans, a radical VNV member, found it difficult to exert any influence during those last months of the war. The main problem was the fact that the Germans continued to confiscate land in the port. The poor food supply also caused dissatisfaction in the city. He protested when necessary and possible, and tried to mediate with the highest occupation authority in Brussels. But all to no avail. The German military interests were an absolute priority at this stage.

Antwerp’s wartime mayor: Jan Timmermans - © Collection of the AMVC-Letterenhuis

After the liberation

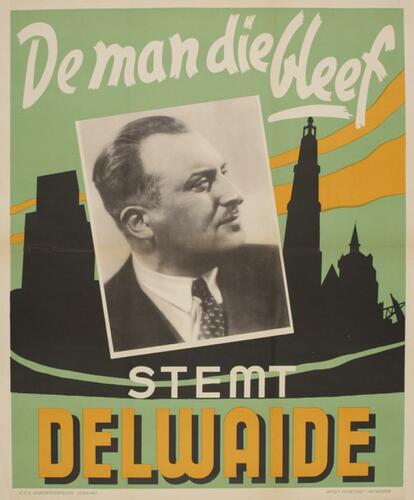

Mayor Huysmans already returned to the city one week after the liberation. Leo Delwaide had been temporarily suspended in view of the ongoing judicial investigation into the accusations against him. This was abruptly closed, without any further action taken, in the course of 1946. The dossier did not mention the persecution of the Jews in the city. None of the aforementioned Antwerp decision-makers were sanctioned after the war for their passive role in the persecution of the Jews.

In a brochure about his actions during the war, Delwaide notes that he assisted those Jews that requested his help. As a result, Delwaide continued to be one of the mainstays of the Christian-democrat Christelijke Volkspartij (CVP) in Antwerp, serving as alderman for the port among others. In the spring of 1945, public prosecutor Baers returned from the concentration camps, where he had been imprisoned since the spring of 1944. He was arrested for helping the resistance. He also resumed his duties after the war.

Like so many others, Oscar Leemans was asked to explain his actions after the liberation. He was appointed municipal secretary during the war. As the head of the city’s administration, he dealt with the occupying forces on a daily basis for four years. After the war, many thorny questions were raised, relating among others to the unification of Greater-Antwerp, several appointments and his relations with the occupying forces. He did not reveal much. As a result, the military judge decided to wrap up the investigation, without any sanctions for Leemans. Moreover, mayor Camille Huysmans, who returned after the war, had expressed his faith in Leemans.

After the war, Leo Delwaide touted himself as the man who did stay in the city - © Collection of the AMVC-Letterenhuis