The war and the occupation caused chaos in Antwerpers’ daily life, curtailing their freedom. Censorship put an end to the freedom of the press while the curfew brought nightlife to a standstill. All lights were switched off on time and German guards were everywhere. But the impact was not the same for everyone. Famine, the much-cursed black market, unemployment and forced labour had more of an effect on some people than on others. And the uncertainty was unbearable for those whose family or friends had been imprisoned. For many people daily life had increasingly become a matter of survival.

Limited freedom

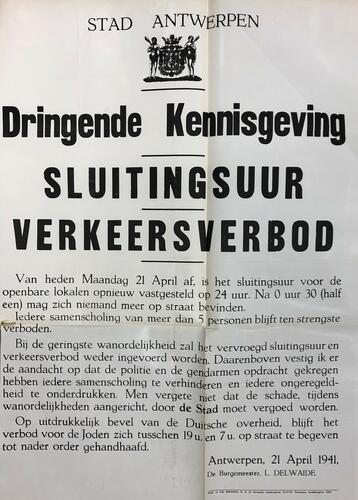

Many Antwerpers remembered the situation all too well from WWI: the military occupation curtailed people’s freedom. A strict curfew resulted in empty streets, places where German soldiers came were off limits and there were plenty of additional controls.

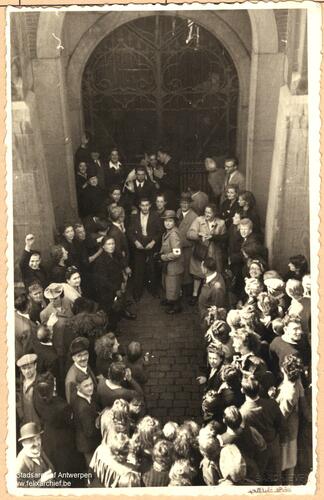

The freedom of movement is severely restricted - © Collection of the Antwerp City Archives

The occupying forces often brought prisoners to the prison in Begijnenstraat. They prisoners were freed on 4 September.

Few civil rights

The dictatorial German occupation regime was rather negligent when it came to enforcing civil rights. Those who did not adhere to the German rules were not guaranteed a fair trial either. As the war progressed, the number of arrests of resistance fighters, Jews and people who refused to work for the Germans and who had gone into hiding increased steadily. Those who were caught risked torture or deportation. Many families experienced unbearable uncertainty about loved ones or friends who had been taken away by the Germans.

No freedom of the press and unreliable information

There was no such thing as freedom of the press anymore. All publications had to be approved by the German censorship and propaganda services.

‘Gazet van Antwerpen’, Antwerp’s local newspaper, was not published during the war years. ‘Volk en Staat’, the newspaper of the collaborating political party Vlaams Nationaal Verbond (VNV) and ‘De Dag’, an Antwerp tabloid, continued to be published, however. They copied German propaganda and defended German or pro-German organisations. At one point, the newspapers even called on the population to go fight on the Eastern Front.

Reliable information became very scarce. The voice of the occupying regime was everywhere. Sometimes even literally, as in the heavily-censored filmed news, which was shown in cinemas before films. Many people therefore took to listening to the broadcasts of the Allies thanks to ‘Radio België’, which broadcast out of Great Britain with the help of the BBC. But this was dangerous as the Germans had made this a crime in early January 1942. Those who were caught or denounced risked punishment.

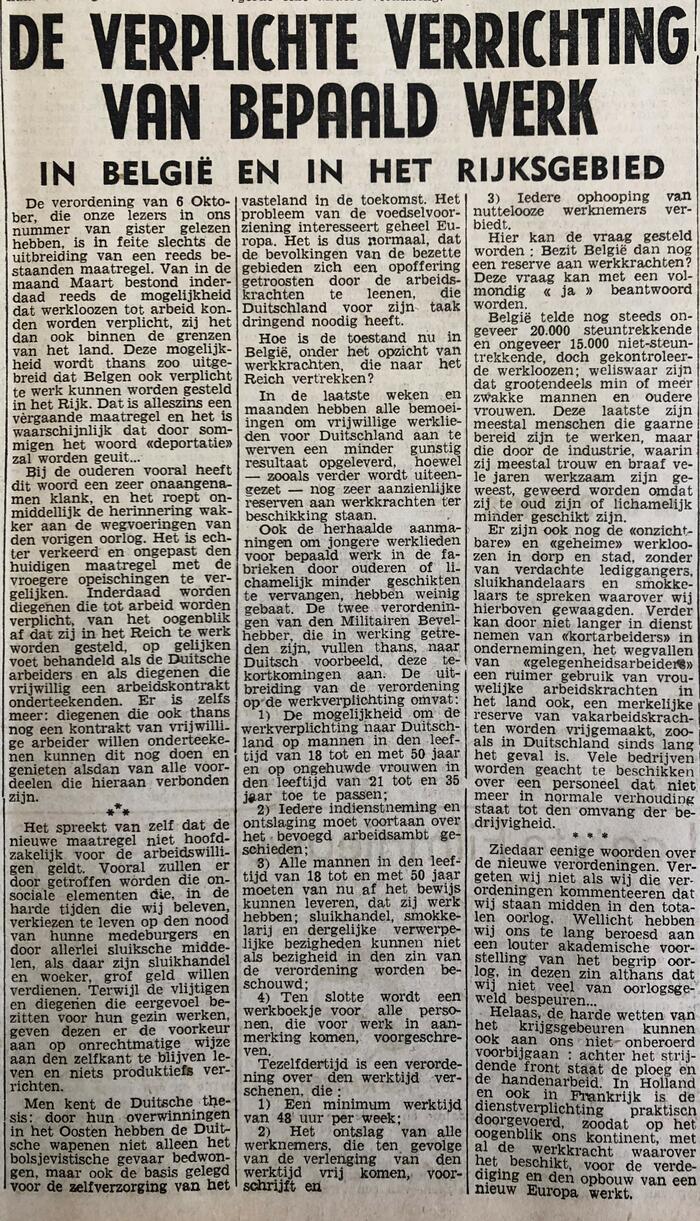

VNV-paper Volk en Staat, 19th of june 1942

Famine and shortages

As a small and sparsely populated country, Belgium was heavily reliant on imports for food. After Belgium was occupied, all imports ground to a halt, causing shortages in the very short term. This was especially apparent in cities from the outset. Most people had such a vivid memory of the famine of 1914-1918 that they were deeply worried about what was yet to come. The first riots and fights in shops erupted as early as May 1940. People wanted to start stockpiling. Prices shot up as soon as the war started.

Couponing

The Belgian population was heavily dependent on the Germans for its food. But the Germans requisitioned a lot of foodstuffs, leaving only a limited share for the population. All basic commodities were rationed. For many months the bread and potato ration was set at 500 g per day per person. This was later reduced to 225 g. Meat rations varied between 35 and 20 g a day. The food quality deteriorated and was terrible. Sometimes food was so scarce that smaller rations had to be distributed.

The rationing gave rise to plenty of new rules and administration. Special coupons and cards were required for many products, determining to how much people were entitled. The rations were rarely sufficient and the queues were often very long.

Price hikes

Prices shot up during the war. According to historians, life was eight times more expensive in 1944, compared with 1939. By 1941, prices had doubled. Famine and shortages had become a daily reality for many people in Antwerp. During the unusually cold and harsh winter of 1941-1942, coal was also in short supply. Heating the house and cooking also became a problem.

The black market

It is an economic mechanism that scarcity leads to price hikes. Which causes people to buy and sell food illegally. The quantities of food that ended up on the black market were enormous. Coveted products were sold under the counter at astronomic prices to the highest bidder. These were often rich people, but more often these products were bought by Germans. Food fraud was also on the increase. Rogue traders started to sell counterfeit or diluted goods.

Survival strategies

Antwerp’s population tried to adapt to the new situation. Many relied on the rural areas to supplement their meagre rations. They preferably bought food from family, and otherwise they just paid the asking price. Those who did not have sufficient means often stole from the fields. People with a garden or rabbits tried to grow vegetables themselves or breed more rabbits. ‘Werk van den Akker’ was working throughout the city to develop new allotments. And most people adapted their diet. An extraordinary good catch introduced Antwerpers to the virtues of eating herring in the autumn of 1942.

Organised food aid

The city council and the official bodies tried to help the population but there was very little margin to do anything because of the strict rules enforced by the Germans. The official food policy failed. A lot of food did not end up where it was intended to and ‘disappeared’ only to resurface on the black market. Winterhulp was the best-known aid and food organisation, supplying soup to the neediest.

Discontent

To some extent, most Antwerpers were prepared to make do with less. But not everyone was affected in the same way by the famine and shortages. When people realised that some other people were not or in any event less hungry and even took advantage of the situation to enrich themselves, discontent soon mounted. The anger was mainly directed at the Germans. Many Antwerpers requested better compliance with the rules and more rigorous action against black marketers. There were popular uprisings, such as on 21 May 1941.

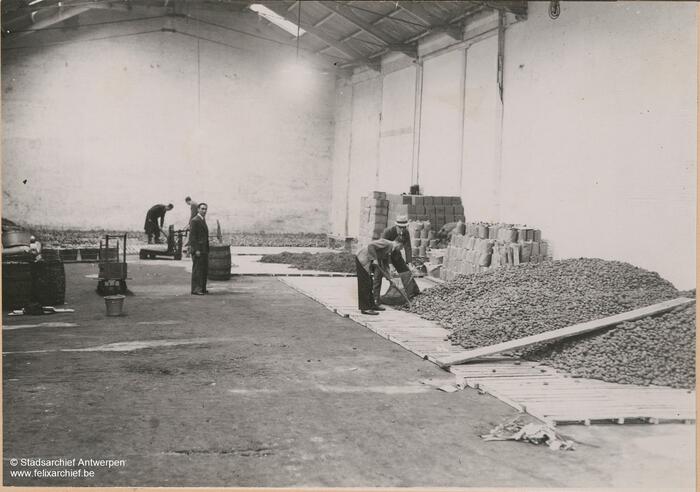

Photo left: For many months the bread and potato ration was set at 500 g per day per person.

Photo right: Many relied on the rural areas to supplement their meagre rations.

Labour

The war almost immediately caused a lot of unemployment. According to historians, there were 500,000 unemployed in Belgium in August 1940, a high figure on a population of 8 million. One year later, this number was already substantially reduced.

Increasing unemployment

The port activities were scaled back substantially during the first month of the war. But elsewhere companies also found it difficult to maintain their pre-war production levels. Some were forced to close. Those companies whose production continued were mainly dependent on the Germans. The major players were all situated in the port and were for the most part metal-producing companies, such as Ford Motor Company, General Motors Continental, Bell Telephone, Cockerill, Béliard, Mercantile, Lecluyse,…and so on.

At the service of the German war economy

Most unemployed were forced to work for the German war economy. The Germans encouraged people to volunteer for work in Germany where there was plenty of work. The Werbestelle, the German employment agency, promised good working conditions and wages in its recruitment campaigns. The extent to which people ‘volunteered’ varied. Many people felt they had no choice if they wanted some form of income. It is unclear how many Antwerpers left for Germany. Research assumes that approximately 224,000 Belgian men left for Germany before October 1942, when forced labour was enforced.

The story of the Merksem-based factory ‘E. Reitz Uniformwerke’ is unique. The German textile company, which produced military uniforms, decided to transfer its entire production from Germany to Belgium. The plant opened in January 1941. Many Antwerp women and girls worked there. By the summer of 1943, the company employed a workforce of 5,000 people.

Forced labour: a tipping point

6 October 1942: a milestone in the history of the German occupation. On that day, the German military government in Belgium proclaimed that all men between the ages of 18 and 50 years of age and all women between the ages of 21 and 35 years of age had to go work in Germany. They later exempted women from this rule. The decision was published six months after the ordinance which ordered Belgians to accept work in Belgium or northern France. Many Antwerpers ended up in German factories, often in terrible working conditions. An estimated 190,000 Belgians were unable to escape this fate.

Going into hiding

This ordinance caused a shockwave in occupied Belgium. Many people still remembered the horror stories of forced labour during World War I. Many young men decided to go into hiding, in rural areas or in more remote and forested areas. In the meantime, the German administration drew up lists of names they found in Belgian municipal registries. Antwerp’s city council and administration refused to collaborate. The German administration requisitioned the workers of companies that were of little or no use to the Third Reich. Later, the Germans would require all men aged 21 years or older to register.

The aversion to the forced labour was substantial. Those who chose to go into hiding faced an equally uncertain and lonely future. Completely disappearing off the radar was difficult. Those who refused to work for the Germans were entirely dependent on the assistance of others, often resistance organisations. Raids and controls took place. Those who fell into German hands during one of these raids risked having to work for the Organisation Todt service. These men carried out heavy-duty military construction for the German army, including working on the fortifications of the Atlantikwall.

The compulsory labour in Germany was harsh. The food was bad, the accommodation terrible. And of course, there was also the constant risk of the bomb raids of the Allies, who were trying to hit the German war economy.

Photo left: Employees of Bell Telephone Manufacturing Company are not forced to work for the German War economy.

Photo right: Censored newspapers such as ‘De Dag’ wrote mitigating articles about the introduction of compulsory work.

Leisure

Public life resumed in the summer of 1940. The German military government, which wanted to create a climate of ‘peace and order’, found this important. Antwerp’s schools reopened. And life continued as usual, to the extent that this was possible. In reality, the impact of the war was felt everywhere, especially from 1942 onwards. But people still found time to enjoy culture and leisure. It was a means of briefly forgetting about the war and daily concerns.

At the occupier’s request

Cultural life in Antwerp resumed from the autumn of 1940 onwards. The military government was adamant about this. The Germans sought to increase their own prestige by supporting the Rubens festivities in November 1940 and the presentation of the Rembrandt Prize soon after. Later the Germans would also organise German theatre and music performances in Antwerp.

Continue or not?

Antwerp’s theatre professionals hesitated. Joris Diels, the director of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Schouwburg (National Dutch-speaking Theatre) in Antwerp, chose the first option. In 1940, however, Diels was already forced to deny his own wife, the Jewish star actress Ida Wasserman, the right to perform.

An evening in the cinema

The many cinemas were cheaper and more accessible to most Antwerpers. They continued to attract huge crowds during the war. There are 56 cinemas in the city. But the Germans also determined the programming there, insisting on a selection of Antwerp, German, French or Italian films. British and American films were banned. Premieres were organised in cinemas that were run by the Germans. Cinema Pathé, on the corner of De Keyserlei and Appelmansstraat, was one example. During the war, its name was changed into Cinema Eldorado. Cinema Roxy in Meir was a ‘soldatenkino’, meaning for German soldiers exclusively.

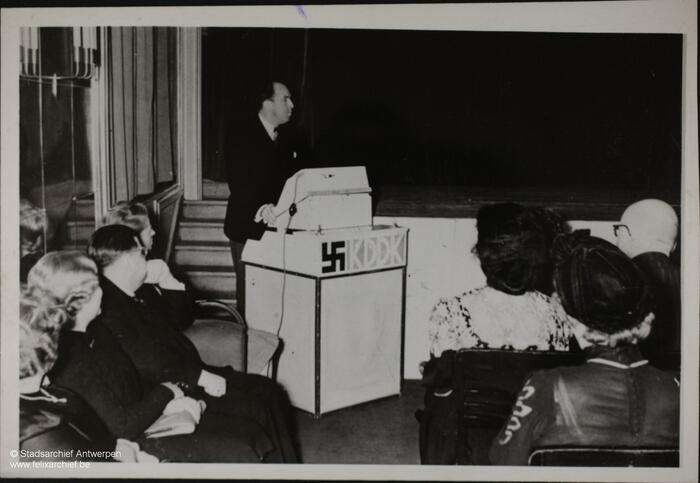

Photo right: The Royal National Theatre performs Het Spel van Dr. Faust.

Photo left: Joris Diels during a speech in Germany.