The Normandy landings

On 6 June 1944, the outcome of the war in Western Europe changed radically because of the Normandy landings. Following D-Day, the armies faced a gruelling advance through occupied France. They only reached the Belgian border on 2 September. British, American and Canadian forces liberated Belgium at a surprisingly brisk pace. After just ten days, they had driven the Germans out of most of the country. Although the Allies initially regarded Belgium as a transit country, they were soon forced to reconsider. Ultimately, Belgium served as a base for military operations against the Germans. As a result, there was still an Allied presence in the region months after the liberation.

British soldiers during the Liberation of Antwerp. (© Antwerp City Archives)

Antwerp and its port played a key role as a logistics and economic hub. This marked a new phase in the war for the city and its population. Unknown soldiers suddenly reappeared on the city’s streets, giving rise to new encounters and introductions to all kinds of special habits and strange customs.

The euphoria of the Liberation

On 4 September 1994, the people of Antwerp spotted their liberators for the first time. A frenzied crowd welcomed the troops of the British Third Royal Tank Regiment, who were the first to enter the city. People hugged and kissed the British soldiers, sharing whatever food and drink they had left with them. People pulled out all the stops in a show of gratitude.

Since 1940, the Belgians had felt nothing but admiration for Great Britain, which had bravely resisted Nazi Germany.

Those who hoped to see the Germans defeated proudly declared that they were 'pro English’. So when British troops liberated Antwerp on 4 September, people were ecstatic. From the outset, it was clear that the British satisfied the locals’ expectations. The people of Antwerp described the Tommies as being robust, healthy men. Many people were impressed at their weaponry and equipment. The noise processions of tanks and trunks inspired awe throughout the city. The contrast with the occupying forces and their inglorious retreat couldn’t have been greater.

A warm welcome

The liberation of Antwerp also provided some much-needed relief for the Allied troops with the Belgians treating the Allies to a noticeably warmer welcome than the French. The relatively smooth advance through Belgium also gave the soldiers a badly-needed break after the fighting in Normandy. After the war, British Lieutenant-General Sir Brian Horrocks described how his men joined in the euphoria of the liberation in Antwerp. In some places, however, people were too quick to celebrate. Grateful Antwerpians took the streets, in their eagerness to welcome their liberators who were still attempting to chase any remaining Germans out of the city.

Foreign soldiers

Antwerp had to live with a military presence for quite some time. In the weeks after the liberation, Americans, Scots and Canadians joined the British troops in the city. The Allies easily conquered the hearts of the local population. The Antwerp priest Theo Greeve fondly described the British as friendly, well-behaved and nice in his diary. The Americans, meanwhile, were loud, uninhibited and jovial. Greeve was especially impressed with the strapping physique of the Americans.

Our heroes

The locals seized every opportunity to show their appreciation for the soldiers. Obviously, they had to overcome the language barrier to do this. By the end of 1944, Antwerp’s newspapers were full of advertisements for English language lessons. Shopkeepers proudly placed ‘English spoken here’ signs in their window displays. In March of 1945, a columnist of Gazet van Antwerpen noted that Antwerp no longer had ‘kappers’ (hairdressers), only ‘barbers’. But whether they spoke English or not, everyone was eager to invite British soldiers into their home. Jan Tiemens from Berchem refers to ‘our Tommies’ in all of his diary entries. Two British soldiers regularly visited the Tiemens family, joining them for dinner at Christmas and on New Year’s Eve, in 1944. When the regiment had to move on and leave Antwerp, the family kept in touch, maintaining a lively correspondence. One of the soldiers even returned to Antwerp to celebrate Jan’s birthday. This shows how Antwerpians lovingly welcomed soldiers from another country into their own family.

British soldiers buying Christmas gifts in the shops in Meir. (© Antwerp City Archives)

The foreign soldiers also did their best to gain the trust of the locals.

They attended remembrance ceremonies and religious processions. On Sunday 8 October 1944, Canadian soldiers carried the statue of the Virgin Mary during the procession in St Paul’s Parish. The arrival of the Allies also heralded the reopening of cultural venues. After four years of living under the strict rules of the German occupying forces, people started to organise dance parties again. Local football clubs played against teams of British soldiers. The new American and British films in Antwerp cinemas always drew large audiences.

Industrial potential

At the same time, the Allies provided a solution to a growing problem, namely the rise in unemployment. In the months after the liberation, Antwerp citizens were given all kinds of jobs to do and played a role in the war production. The Allied command soon realised that the region had plenty of industrial potential, ensuring that several factories were able to resume their production. The Ford plant hired new workers to produce and repair American trucks and jeeps. Soon after, the port reopened, which significantly boosted the number of people who were employed by the Allied Forces. By early March 1945, the Allies had recruited a workforce of 20,000 workers in Antwerp’s port.

The continuing war

Initially the mood in Antwerp was upbeat when the British troops arrived. But this soon turned into disappointment during the next few weeks. On 4 September 1944, many locals were convinced that the liberation marked the end of the German occupation and the end of the war. Soon they realised this was not to be.

The country soon found itself under a new type of occupation, because of Belgium’s strategic military importance. Once again, a foreign army imposed several restrictions on Antwerp’s population. They regulated the use of vehicles, imposed a curfew and require citizens to blackout their windows. In addition, the Allied armies also requisitioned several buildings. Initially, they limited themselves to those buildings that had been previously confiscated by the Germans. But this soon proved insufficient. Countless factories, warehouses, schools and hotels were requisitioned for the military campaign. The city appealed to each household, asking people to make available billets or living quarters for British officers.

Food shortages

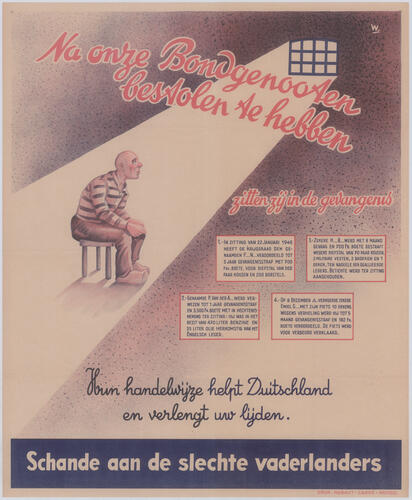

Above all, the ongoing food shortages proved the biggest source of disappointment. In the months after the liberation, bread, margarine, vegetables and meat became even scarcer. By time winter came, there was almost no coal to be found in the city. There was also a gas and electricity shortage. This hopeless situation forced people to resort to illegal action. The Allies complained almost continuously about thefts by the local population. The British military police and the local police took strong action in response. The British government distributed posters throughout the city warning Antwerp’s populations about the consequences of such actions. The majority of the population disapproved of this kind of crimes against the Allies.

Poster of the British military authorities discouraging the theft of military supplies. (© Antwerp City Archives)

Discord among the population

Notwithstanding the enthusiastic welcome of the Allies, the population also felt resentment. The first signs were apparent already on Liberation Day. Although everyone greeted the liberating forces with great enthusiasm, Antwerp’s womenfolk gave them an especially warm welcome. Many women threw themselves into the arms of these foreign soldiers.

On 13 September 1944, the Catholic Gazet van Antwerpen published an article condemning this ‘khaki madness’. The article condemned ‘de houding van zoovele zoogezegd goed opgevoede meisjes, die staan te drentelen en giechelen, zich op te dringen en verliefd te doen tegenover de nieuwe soldaten.’ (the attitude of so many supposedly well-behaved girls, who loll around giggling, imposing themselves upon and falling in love with the soldiers). All this fraternisation came with consequences. Along with the number of sexual contacts, the number of STDs also sharply increased.

The newspapers warned against sexual promiscuity and more. While Antwerp’s population had to make do with less and less, the British army made sure its soldiers had sufficient supplies. People often begged soldiers for cigarettes and chocolate, which were of much better quality than their Belgian counterparts. Petrol was also very popular. The local authorities worried that the Allies would come to see the population as bums, which is why they asked Antwerpians to refrain from doing this.

The exodus

The influx of soldiers in Antwerp continued long after the war had ended. The exodus after 8 May 1945 was generally quite chaotic. The US military devised a complex system for deciding which soldiers could return to America and who was sent to Asia as part of the war effort. Until the decision was made, hundreds of thousands of soldiers bided their time in ports across Western Europe, including Antwerp, until their departure. The US army established a huge transit camp on the left bank of the Scheldt, called Camp Top Hat, for this purpose. The camp could accommodate and entertain 16,500 soldiers. The Allied exodus ended in the spring of 1946.

Mapmaker Hugo Van Kuyck

Hugo Van Kuyck was an Antwerp mapmaker who drew maps for D-Day. He played an important in the Normandy landings. Find out more about his story by clicking his name. (story in Dutch)