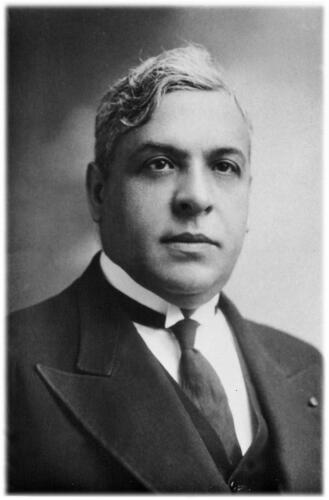

Portuguese diplomat (1928 - 1938) who saved Jewish families in Antwerp from persecution.

I would rather stand with God against Man than with Man against God (1940)

(photo: Sousa Mendes Foundation)

When World War II broke out in the summer of 1940, Aristides de Sousa Mendes had been living in the southern French city of Bordeaux for two years where he served as Portuguese consul. In the previous years he held the same position in Antwerp (January 1928-1938). He lived in Rubenslei during his time in Antwerp, making many friends there.

Soon after World War II broke out, the German invasion gave rise to unprecedented flows of refugees. The Red Cross estimated that there were approximately 6 million displaced people on the move at the time. The majority came from countries that were invaded by the Germans, including approximately 2 million Belgians. They included civilians who feared the violence of war, political refugees and Jewish families. Many of the travelled through the south of France and Spain. They all sought to get to ‘neutral’ Portugal, from where they could sail to Palestine, the United States or Latin America.

This was a complicated route to take, as the authoritarian Portuguese regime made it almost impossible for anyone to enter the territory. Aristides de Sousa Mendes decided to defy the politics of his country, choosing to follow the voice of his conscience instead. From mid-June 1940, Sousa Mendes, who served as the Portuguese consul in Bordeaux, issued an entry visa to anyone wishing to reach Portugal. He did not distinguish between nationality, religion or race. Thousands of refugees thus escaped Nazi persecution, including several Antwerp families. Sousa Mendes paid a heavy price for his decision. His career came to an abrupt end. His children were unable to make a life for themselves in totalitarian Portugal in the 1950s and 1960s. He died, destitute, in 1954.

Sousa Mendes’s children and grandchildren received a certificate of honour in the name of their father who was recognised as “Righteous Among the Nations” at the Yad Vashem (1967).

Photo: Sousa Mendes Foundation

Although Israel recognised the importance of his actions as early as the 1960s, it would take until the 1980s and the collapse of the dictatorship in Portugal for his homeland to recognise his legacy.

In the summer of 1940, Aristides de Sousa Mendes was living in Bordeaux. The strict Portuguese regulations did not leave him much room for manoeuvring. Now and then he made an exception, granting a visa here and there. But Sousa Mendes was careful as he had no intention of getting caught. Soon, the situation became even more desperate, however.

Large groups of refugees camped on the consulate’s doorstep. He had to make a choice. From 17 June 1940 onwards, he gave a visa to anyone who asked for it. He even set up an assembly line, with the help of consular staff and his family, signing visas en masse with people lining up by the thousands into the street. By the time the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs finally cottoned on to what he was doing, it declared any documents issued by Sousa Mendes null and void.

On 24 June 1940, the authoritarian Portuguese president António Salazar recalled his consul to Portugal. Aristides de Sousa Mendes took his time, finally arriving on 8 July. Once there, he defended his actions during disciplinary proceedings, stating that they were motivated by humanitarian considerations. A devout Catholic, he refused to let the refugees fall into German hands as this would have endangered the lives of many of them. He famously said that he would rather stand with God against man than with man against God.’

On 30 October, Salazar personally pronounced the consul’s sentence. He was immediately removed from his post, paid half his salary for a year, after which he was forced to retire from Portuguese diplomacy. Aristides de Sousa Mendes died penniless in 1954, at the age of 68.

Renowned Holocaust historians have described his actions as ‘probably the largest rescue operation by a single individual during the Holocaust’. The actual number of people that he saved is not known with certainty, but he is said to have issued tens of thousands of visas, including to 10,000 Jewish refugees. As such, Sousa Mendes made a substantial contribution to Jewish survival during the Holocaust.

International recognition for Sousa Mendes’s actions soon followed. In 1966, Yad Vashem honoured him as one of the Righteous Among the Nations, a title used to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews from extermination by the Nazis. In Portugal, a scathing report was published in 1974 (after Salazar died and the authoritarian regime that followed him was overthrown), condemning his treatment by Salazar. In 1987, the Portuguese president apologised to the Sousa Mendes family on behalf of his government. One year later, the Portuguese Parliament unanimously voted a law to admit Sousa Mendes back into the consular service and promote him to the rank of ambassador and repairing the injustice.

Fleeing from war into uncertainty: the Deutsch family

Bernard Deutsch and his family left Antwerp in 1940. They managed to reach Portugal and New York, their final destination, thanks to a visa issued by Sousa Mendes.

(photo: FelixArchive Antwerp)

The Jewish Deutsch family from Antwerp found themselves among the many refugees that were left stranded in the south of France in the summer of 1940. In the years before the war, four of the five sons were employed in the Antwerp diamond industry.

Like so many others, they fled the city in May 1940. Their destination? Portugal. Once they arrived in the south of France, they realised that the Spanish border was closed. Under the dictatorship of General Franco, Spain did not admit refugees. However, the government was obliged to let refugees with a Portuguese entry visa travel through the country by train or private car to get to Portugal. Thanks to a Portuguese entry visa issued in Bordeaux by Sousa Mendes, the Deutsch family finally managed to reach Portugal. But time was running out there too. Their visa only entitled them to temporary residence in Portugal.

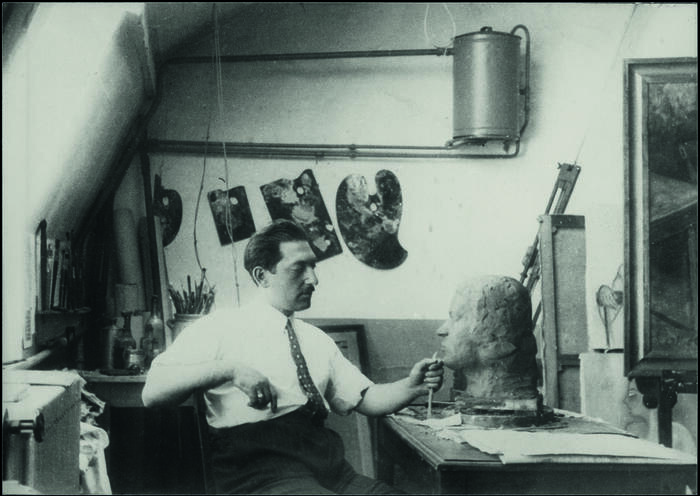

The painter Carol Deutsch decided to remain in Belgium. In 1943, he was arrested and deported by the Germans, together with his wife.

Photo: Collection of Mu.ZEE Ostend

The regime led by António Salazar had tightened its refugee policy for some time already. Consuls, and therefore Sousa Mendes, could no longer independently issue visas to stateless persons or Jewish persons who were unable to prove that they could return to their country of origin. The fact that Portugal gradually became a safe haven for thousands of war refugees in the summer of 1940 is partly due to the actions of one man: Aristides de Sousa Mendes.

The Deutsch family, who were stuck in Porto, waited in fear. Even though they had a valid visa for one of these destinations, tickets for ships or planes were expensive and availability limited. Bernard Deutsch and his family managed to reach the United States with the help of family. They boarded a Greek ship, the Nea Hellas, arriving in New York on 12 September 1940, exactly four months to the day after they fled Antwerp. They were fortunate. One of the brothers decided to stay in Belgium. Carol Deutsch met with a different fate. He moved to Ostend before the war, frequenting the artistic circles around James Ensor. He married Fela, also a Jewish refugee, with whom he had a daughter. The family decided to go into hiding as the occupying forces issued increasingly stringent anti-Semitic measures. In September 1943, Carol and his wife were arrested. On 20 September, they were deported from the Dossin Barracks to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Fela was selected for medical experiments. Her fate remains unknown to this day. Carol was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp and later to Buchenwald, where he died of exhaustion on 20 December 1944. Their daughter survived the war, in hiding, in Belgium.

This shows how one person’s actions can make the difference between life and death. Without the valiant efforts of Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the entire Deutsch family, and many others with them, would have perished like Carol and his wife.

Read more about Aristides de Sousa Mendes and the people he saved by issuing them a visa. The Sousa Mendes Foundation was able to identify several of these people through research at the FelixArchive (Antwerp).