On 27 January, we celebrate Holocaust Remembrance Day, an international memorial day to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust. The date was purposefully chosen. On 27 January 1945, Soviet troops liberated the Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The international commemoration of Holocaust victims on 27 January was instituted relatively recently. The United Nations General Assembly unanimously adopted a Resolution on 1 November 2005 in New York urging the nations of the world to observe this day on 27 January.

27 January 1945: Auschwitz-Birkenau

On 27 January 1945, Soviet troops walked through the gates of Auschwitz-Birkenau. By this time, the camp had been abandoned by the SS for more than a week. In the weeks leading up to the liberation, they had received orders from Berlin to destroy all the evidence.

The entrance gate to Auschwitz - Birkenau (Wikimedia Commons)

The Red Army was advancing, which is why the German commanders began blowing up buildings. At the same time, the camp leaders also began evacuating the camp. Only prisoners who were still able to walk were moved from the camp. Those who were too sick, weak or dying were left behind. A mass forced evacuation of 56 to 58,000 prisoners to other camps ensued. Historians estimate that just under half of these poor souls did not survive this gruelling death march. The prisoners suffered due to the freezing cold, exposure to the elements, and strenuous physical exertion. Many were so weakened by life in the camp that they simply died en route. Others who slowed the pace, were unable to keep up with it or attempted to escape were shot on the spot. The German orders were very clear: no evidence, no witnesses.

When Soviet troops finally entered the camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, they found approx. 9,000 camp survivors. The Germans reasoned that they were in such bad shape that they would probably die during the evacuation. The starving and weakened prisoners were immediately set free. But their suffering was far from finished. The Soviet troops had not expected to encounter such a dire situation. It took them days to install the first field hospitals and administer the necessary first medical care. Unfortunately, for many victims, their assistance came too late.

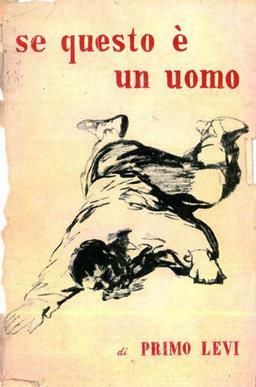

The Italian writer Primo Levi was one of the many sick who were left behind in the camp by the Nazis.

He fought off scarlet fever in the infirmary and managed to survive the camps. After the war he wrote one of best-known and most widely read camp testimonials: ‘Se questo è un uomo’ (If This Is a Man). In it Levi describes the days between the evacuation of the camp and its liberation by the Red Army in great detail.

‘We all said to each other that the Russians would arrive soon, at once; we all proclaimed it, we were all sure of it, but at bottom nobody believed it. Because one loses the habit of hoping in the Lager (camp), and even of believing in one’s own reason’.

(…)

‘Like joy, fear and pain itself, even expectancy can be tiring. Having reached 25 January, with all relations broken already for eight days with that ferocious world that still remained a world, most of us were too exhausted even to wait.’

‘If this is a man’ – Primo Levi (Wikimedia Commons)

27 January 1945: Antwerp

In 1944, the German police service declared Antwerp to be 'Judenrein’ or ‘cleansed’ of Jews. The few remaining Jews in Antwerp at the end of January 1945 managed to evade German officers and their local collaborators because they went into hiding. After the city had been liberated, they could finally leave their hiding places. In the weeks and months after the liberation, several Jewish displaced persons returned to Antwerp. They gradually tried to organise themselves under the lead of several iconic figures of the Jewish resistance movement. They had several needs: finding their lost family and friends, recovering property that had been plundered, finding food.

The Jewish resistance fighter Jozef Sterngold played an important part in the rebuilding of the Jewish community in Antwerp.

Sterngold was an active member of the Joodsch Verdedigingscomiteit (Jewish Defence Committee), which was renamed Comité ter Verdediging van de Joodsche Belangen (Committee for the Defence of Jewish Interests) after the war. In his post-war memoirs, he described the many problems he encountered including housing. The houses of Antwerp Jews were often occupied by other refugees, war victims or even former neighbours. Many houses had also been looted by German police forces, collaborators or other Antwerpians. Moreover, the British Allied administration in the city requisitioned the empty houses, including those of the Jews, to billet Allied soldiers there.

Sterngold: ‘My first concern after the liberation was for my protégés, who lived in the city in hiding. Most of them wanted to resume a normal life as soon as possible. But where would they go? Their houses had been systematically looted and the furniture and their belongings sent to Germany. Their houses were now occupied by non-Jews, made available to those whose homes had been destroyed by the bombs of the Allies.’

Jozef Sterngold (Collection of Kazerne Dossin Holocaust Memorial)

Together with other relatives in Antwerp, the Jewish survivors tried to keep their spirits high even though the uncertainty, the lack of information, and the terror were a terrible burden to bear by the end of January 1945. Most of them had no idea what had happened to their family members, friends, and fellow sufferers. Early newspaper reports implied the worst. Soon after, reports of the horrors in the camps trickled through more systematically.

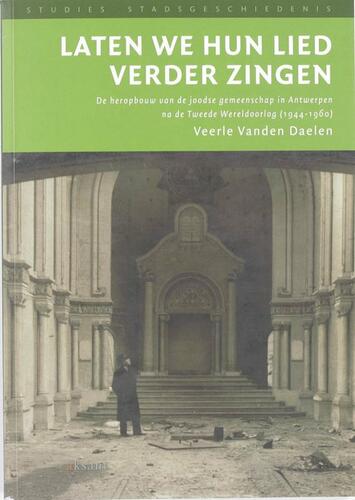

Historian Veerle Vanden Daelen (Kazerne Dossin) aptly describes this in her study on the rebuilding of the Jewish community in Antwerp.

Historian Veerle Vanden Daelen: 'The Jewish victims were completely confused, psychologically. They struggled with the uncertainty about the fate of their family and friends, experienced guilt because they had survived and suffered trauma from the camps or going into hiding. They would need much more than food and drink to recover.’

Book cover of 'Laten we hun lied verder zingen. De heropbouw van de joodse gemeenschap in Antwerpen na de Tweede Wereldoorlog (1944-1960)', Veerle Vanden Daelen, Amsterdam, 2008

At the end of January 1945, Antwerp had been freed from German occupation for five months. But the war was far from over and Antwerpians feared for their lives on a daily basis because of the German V-weapons. On 27 January 1945, twelve V-weapons fell on the territory of Greater Antwerp. Fortunately there were no fatalities. Unfortunately there was not much cause for cheer. A day later, the Germans resumed their attack, with 48 civilians dying according to the police.

The spring of 1945: the return to Antwerp

When Jews and other deported Antwerp residents finally returned from the camps, people finally realised what a gruesome fate they had endured. Most of them arrived in Antwerp’s Central Station in the spring of 1945. An aid station of the Red Cross was jointly responsible for their reception. In March and April 1945, the Red Cross provided aid to 162 and 3,790 people respectively. This increased to 19,391 and 9,935 returnees in May and June. From July 1945 onwards, the numbers decreased again (3,109). While these figures are by no means complete, they do illustrate the chronology of the repatriation in the spring and summer of 1945.

One of the survivors was 20-year-old Antwerp Jew Tobias Schiff.

In ‘Terug naar de plaats die ik nooit heb verlaten’ he writes the following about his return to Antwerp from Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. That is where he ended up after a long and horrific peregrination through Auschwitz-Birkenau and Kamp Dora. Upon his arrival in Mol, a taxi took him to Antwerp’s Central Station. He says this about his arrival in the station:

‘The people gave us money because we were still wearing our camp outfits. Some even wept when they saw us.’ He was soon recognised as he made his way to the Jewish neighbourhood and the Tachkemoni School. He moved to Brussels soon after to live with his family.

Tobias Schiff (left) upon his return to Antwerp (Collection of Kazerne Dossin Holocaust Memorial)

Many returned Jews had mixed feelings about this period during and after their repatriation. There was widespread relief and joy because the war had finally ended. At the same time, they mourned the family, friends and acquaintances that they had lost. Moreover, not everyone was able to return to Belgium immediately. Some, such as the resistance fighter Leopold Flam, who survived deportation to Buchenwald, returned home within two weeks of being liberated. Others had to wait much longer. The process was much more laborious for Jews who did not have Belgian nationality or who were ‘stateless’ because of the identity checks. The travel conditions in war-ravaged Europe were not always optimal either.

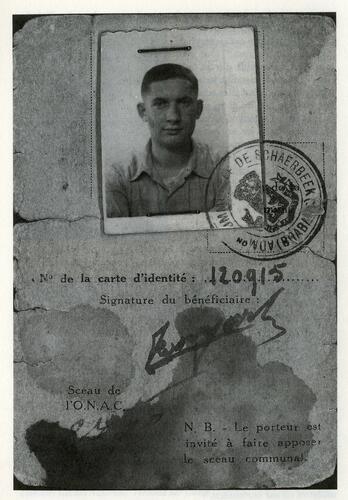

Israel Rosengarten’s book about his repatriation to Belgium bears witness to this.

Rosengarten was imprisoned in Buchenwald when American soldiers liberated the camp on 11 April. When the evacuation started a few weeks later, he was informed that he could return to Belgium by plane: ‘I was very excited, ready to leave and bid this horrific place farewell. But just as I was about to board the plane, the Belgians in charge of the organisation (…) came to the conclusion that I could not be repatriated. (…) They said that it was not clear whether I was really a Belgian. I had been registered as coming from Belgium but my father came from Poland. And that is how they started to question my nationality.’

Israel Rosengarten would be forced to spend another two weeks in the camp. A train (‘a freight train, with ramshackle, covered freight wagons’) brought him to Namur and onwards to Brussels-South. By the end of 1946, 20-year-old Israel Rosengarten finally decided to return to Antwerp. He found a house in Bloemstraat: ‘Just one door down from where I had lived as a child in 1930.’

ID card of Israel Rosengarten 1945 (from: Israel Rosengarten 'Overleven. Relaas van een zestienjarige Joodse Antwerpenaar', Antwerp, 1996)