Antwerp, the end of August 1945. Four months had passed since the end of the war. But its after-effects were still very much felt. The material damage, caused by fighting during the city’s liberation or by the impact of V-weapons and other bombs, had created a scarred city. The human suffering caused by the war in Antwerp was much less visible.

The summer of 1945 did not necessarily bring relief for the family members and friends of deportees and other prisoners. They waited anxiously, hoping to receive good news, often against their better judgement. At the end of August and in early September 1945, the hopes of those families who loved ones had not returned, faded as the repatriation drew to a close. They no longer could ignore the losses they had suffered. The war victims who did not return and from whom nothing more was heard were listed as ‘missing’ from then on.

The quest for the missing: an international matter

After the repatriation of the survivors, the Belgian state had to take the next hurdle: tracing and identifying missing persons and checking whether they had died. In the winter of 1945, the government established a ‘Bureau National de Recherche’ for this purpose, in addition to the existing Belgian repatriation commission.

The office got off to a rough start. By 1947-1948, however, things were running smoothly. The rough start in the beginning was not just due to a lack of experience, expertise and resources.

The post-war context of the Cold War only complicated matters even more. At the time, Germany was divided into four zones that were occupied by Great Britain, France, the United States and the Soviet Union, respectively. Each of these countries established its own investigative service, which failed to exchange data with each other. It would take until the end of the 1940s before a proper international cooperation was established. Unsurprisingly, this was done under American supervision and information was solely exchanged between Western countries. The Cold War prevented any contacts with services operating within the Soviet sphere of influence. The end of this Western cooperation, the ‘Arolsen Archives’, still exists to this day and is an essential tool for historical research into victims of the Nazis.

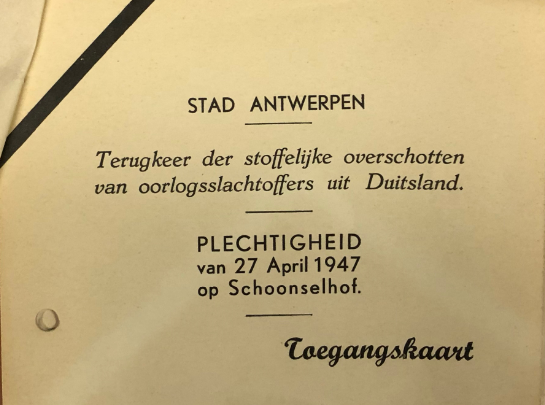

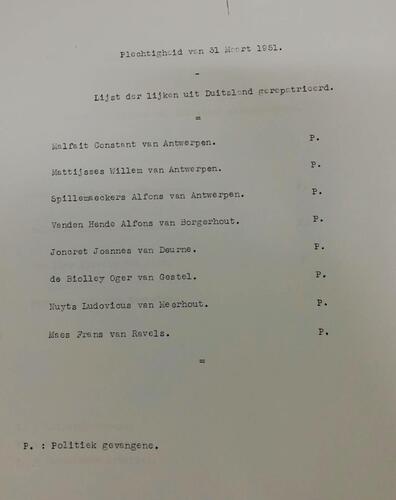

After the remains had been identified, they were repatriated to Belgium, and a ceremony organised upon arrival - © Archives of the Red Cross Antwerp

Repatriation by the Red Cross of the bodies of Antwerp political prisoners - © Archives of the Red Cross Antwerp

Collecting information

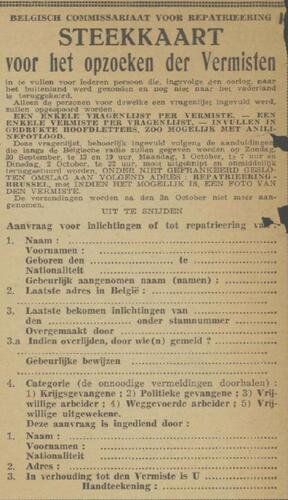

On 20 September 1945, Minister Adrien van den Branden de Reeth who was responsible for War Victims gave a speech on the radio. He spoke of the ‘tremendous uncertainty about the fate of many who have not yet returned to their hearths’. In the autumn of 1945, he organises a ‘national census of the absent’ to locate (and if possible, repatriate) the missing. The idea was to create a central index card register of missing persons. During his speech, he encouraged the parents and friends of the missing to complete questionnaires.

The Gazet van Antwerpen of 29 September 1945 publishes the questionnaire of the Ministry of War Victims - © Digital Archive of Gazet van Antwerpen

The ministry received 25,000 in the first week after the broadcast. One year later, the ministry organised a travelling exhibition in Belgium of the photos of missing persons that had been submitted, in the hope of finding new information.

By the end of 1945, the Ministry of War Victims had data on more than 30,000 missing persons, i.e., 20,000 Belgians and 10,200 foreigners who resided in Belgium before the war. In the following years, the number of missing persons continued to rise. Interestingly enough, 'only’ 10,200 non-Belgians were reported missing by the end of 1945. This is striking given that more than 30,000 Jews from Belgium (who rarely had Belgian nationality) were murdered. In many cases, there was no trace of entire families.

The only choice people had in that case was to report their relatives as missing.

The relatives of these Jewish victims often had no idea what had happened to their loved ones or lived abroad. From 1948, the number of Jews reported missing increased sharply, however. Organisations such as ‘Aide aux Israélites Victimes de la Guerre’ assisted the few surviving relatives, helping them to trace the missing and identify the deceased. At the end of 1950, the number of missing non-Belgians stood at 21,614.

Absent, missing and deceased

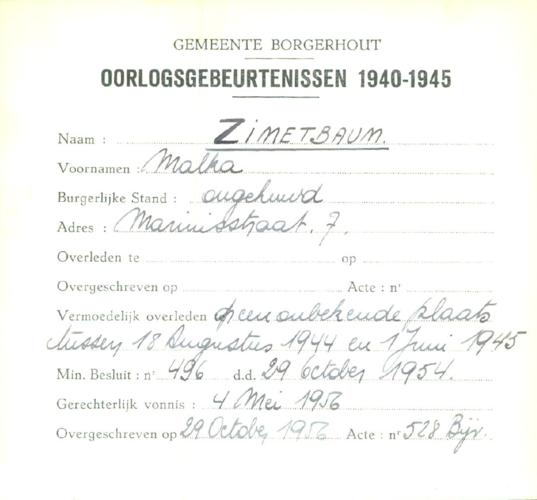

Determining whether someone had died was extremely important for the next of kin, from an emotional point of view. But a relative’s death also had ‘practical’ implications. The municipal services could not draw up a death certificate if they were unable to determine whether a person had actually died - for example because the missing person could not be found. Without this death certificate, the next of kin and beneficiaries could not appoint guardians, dissolve marriages, claim inheritances, receive assistance to war victims and faced all kinds of other financial and administrative issues.

The Belgian government soon realised that the existing legal framework was insufficient and decided to intervene with the Act of 20 August 1948 on the 'judicial declaration of death’. Henceforth, the Minister for War Victims and the courts of first instance could also officially establish the death of a person who died during and as a result of the war, either with 'ministerial decree of presumed death’ or with a ‘judicial declaration of death’.

The Jewish lawyer and camp survivor Marcel Marinower assisted several Jewish families. In early 1950, he published an article on the relevance of the Act of 20 August 1948. He died in 1962 as a result of the hardship he suffered in the camp. - © Rechtskundig Weekblad (Intersentia)

Ministerial decree and judicial ruling regarding the death of Mala Zimetbaum - © Antwerp City Archives

The legislation applied to all persons who had gone missing as a result of the war. So the law did not just pertain to victims of Nazi persecution.

The descendants of voluntary workers and collaborators, such as Eastern Front fighters who died there and from whom nothing more was heard after the war, could also invoke this legislation. Before the minister or judge determined the (presumed) death, a thorough investigation had to be conducted. The Belgian state was keenly aware that collaborators, workers and some deportees were not intent on returning to Belgium after certain events.

De Antwerpse specificiteit

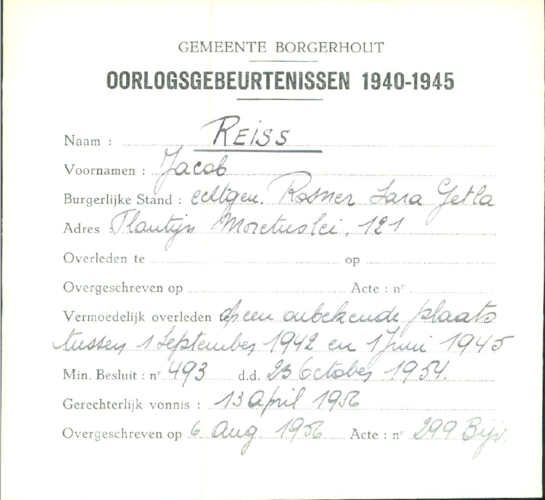

Op 27 januari 1956 doet de Antwerpse rechtbank van eerste aanleg uitspraak in het dossier over de Poolse familie Reiss. Deze 7-koppige Joodse familie is in de herfst van 1938 uit Berlijn weggetrokken, op de vlucht voor het nazisme. Hun tocht brengt hen naar Antwerpen. Jacob Reiss en Sara Gitla Rosner nemen er samen met hun vijf kinderen Manfred, Adolf, Sonja, Paula en Beila (de oudste is 10 jaar, de jongste pas 2 maanden) intrek in de Draakstraat. Na het eerste oorlogsjaar verhuist de familie naar Borgerhout, op de Plantin en Moretuslei (121). In de nacht van 28 op 29 augustus 1942 slaat het noodlot toe. De bezetter pakt de voltallige familie op tijdens een razzia. Ze zijn niet alleen. Ook elders in Borgerhout laadt de bezetter nog eens 300 Joodse inwoners op. Drie dagen later voert het 7de konvooi de familie Reiss naar Auschwitz. Geen van hen overleeft de deportatie. Het vonnis van die 27ste januari 1956 bekrachtigt dit. Officieel zijn zij allen overleden op 01/09/1942 ‘te vier en twintig uur’ en op een ‘onbekende plaats’.

Jacob Reiss - © Antwerp City Archives

If the exact date could not be determined, the court - symbolically - opted to use the deportation date.

The Antwerp Court of First Instance issued no fewer than 11,363 death certificates in the years between 1945 and 1965. Although the figures apply to the entire judicial district of Antwerp, the majority of these 11,363 persons lived in the Antwerp urban agglomeration before and during the war. In Borgerhout alone, civil servants counted approximately 2,609 missing inhabitants, including the Reiss family. It is no coincidence that the figures for Antwerp are so high. The majority of the missing are Jews, of whom an estimated 15,000 disappeared from Antwerp during the war.”

Today, these and other documents constitute a valuable source for research into the names of Antwerp’s war victims. As a result, the Reiss family, like so many others, was given a place on the monument with the names of war victims.

Ministerial decree and judicial ruling regarding the death of Jacob Reiss - © Antwerp City Archives